This essay was originally published in “Der Widerstand” (1930) under the title Kriegerische Mathematik, and republished in the collection “Blätter und Steine” (1934). With a focus on war tactics and technology it can be seen as an addition to “Total Mobilization”.

In the age of technology, it could only have been expected that the means and methods of warfare would undergo more rapid and profound changes than what has otherwise been observed in the shifting hostile encounters that take place between men. Great events confirm that the forebodings of the influence of technology on warfare have been well-founded. There was no shortage of surprises during the world war. Nevertheless, change holds a certain constancy, so we can speak of development rather than a sudden revolution in the nature of warfare.

In war, as in all fields of human activity, conservative and revolutionary currents flow side by side. The secret of victory is often sought in the magic of the weapons that secured the battles, and after the war is won an army may believe that it still holds the recipe that guarantees victory. On the other hand, no area of experimentation can be more dangerous than in war, because here fate invades life more intensely than anywhere else, giving each step a decisive and irreversible significance. This is what makes any innovation based on purely theoretical considerations, and lacking a solid core of experience, unsettling. This is why new means and new forms are not approached with the vigour with which military utopias, such as those that existed in large numbers before and after the world war, are created. In most cases a new weapon, a new type of combat regime only gradually appears on the landscape of war – hesitantly and initially limited to small theatres of warfare.

In addition, war is an exceptional situation, and the use of weapons is interrupted by long periods of peace. While it is true that weapons and training also develop during these periods, they are not reinforced by the most vivid experiences of battlefield events.

It is true that the experience of war constitutes the capital that nourishes the soldier’s view of war in peacetime, however, the value of this capital diminishes in the same measure that the war recedes into the past. The inner life of war is very soon forgotten, thirty years of peace mark it as a legend, what is unimaginable.

Yet, at the same time, the possibilities of warlike conflicts are constantly growing, for war is not a state entirely subject to its own laws, but another aspect of life which rarely appears on the surface yet is intimately connected with it. Just as war expresses not a part of life but life in all its violence, so this life is itself grounded in warlike nature. The possibilities of war are therefore unceasingly nourished by peace – and as times change, so does war.

There is, however, no mistaking the certain delay with which the era brings a certain military expression to bear. Thus there is a time-lag between the invention of gunpowder and the use of firearms, between the use of steam power and the advent of the first engine-driven warships. The advantages which nations gain over each other during this period are usually small, but significant in nature.

The experience of warfare that Germany had before the outbreak of the world war came essentially from the Franco-German war. The spirit of the victorious tradition found its expression in a justifiably confident fighting power, expressed in notions of open combat, in the mobility of artillery, in the strength of cavalry, and in the strategic ideal of the image of an all-out battle of annihilation.

On the other hand, the enormous technological advances which characterised this period also led to an extraordinary increase in the effectiveness of firepower and hence the means available to the defender. The growing firepower that could oppose movement was most evident in two events which took place on the margins of civilization, but which nevertheless conveyed the changing conditions under which an encounter between European armies would take place. The Boer War, for example, already involved the gradual disintegration of the fighting masses and the painful exploitation of the terrain. The wide spaces, swept by invisible fire, produced that monotonous and dangerous landscape whose atmosphere has been described as the “desertedness” of the battlefield. The effect of increased firing was even more striking during the Russo-Japanese War. On the battlefields of Manchuria, one can see in minute detail the conditions of positional warfare, the characteristic feature of which is that both opponents, who possess maximum firepower, are practically immobilised.

This asymmetry between the modified action of weapons and forms of movement - which had not yet been adapted to, let alone surpassed - continued on a gigantic scale into the World War. Three main areas can be distinguished: in the first, the old-style movement searches in vain to come to a decision. The second is characterised by absolute domination of fire. The third tries to reinvigorate the movement with new methods.

These three phases do not follow each other in time; rather, although of different significance, manifest themselves in a manifold of shades side by side. Thus the war of movement, as it was conceived at the beginning of the war, continues throughout the entire campaign. The variety of counterattacks in the various theatres of war meant that the fronts were constantly in flux. In Russia, in the Balkans, and even in Italy, positional warfare manifested itself only as a break which could easily be interrupted by a new offensive if sufficient forces were available. But where war is waged by all means of large-scale technology, in the decisive theatre, i.e. the Western Front, events unfold according to strict laws, and the three phases of war diverge from each other in immediate succession.

Here the war of movement, as it corresponded to traditional perceptions, was soon replaced by the solidification of the fronts. When young volunteer regiments, formed from the best elements, collapse under machine-gun fire, as in Flanders, and when old trained troops are nailed to the ground after only a few kilometres while trying to resume their advance into the depths at individual sections of the front, it is clear that the severity which begins to paralyse movement cannot be explained by a lack of spirit or will, but only by the fact that the quality of movement can no longer endure the increased gravity of fire. It was not only the German armies that suffered this fate - the French élan, the English cold-bloodedness could no longer overcome the fiery zone that confronts them in an increasingly dense and deadly manner.

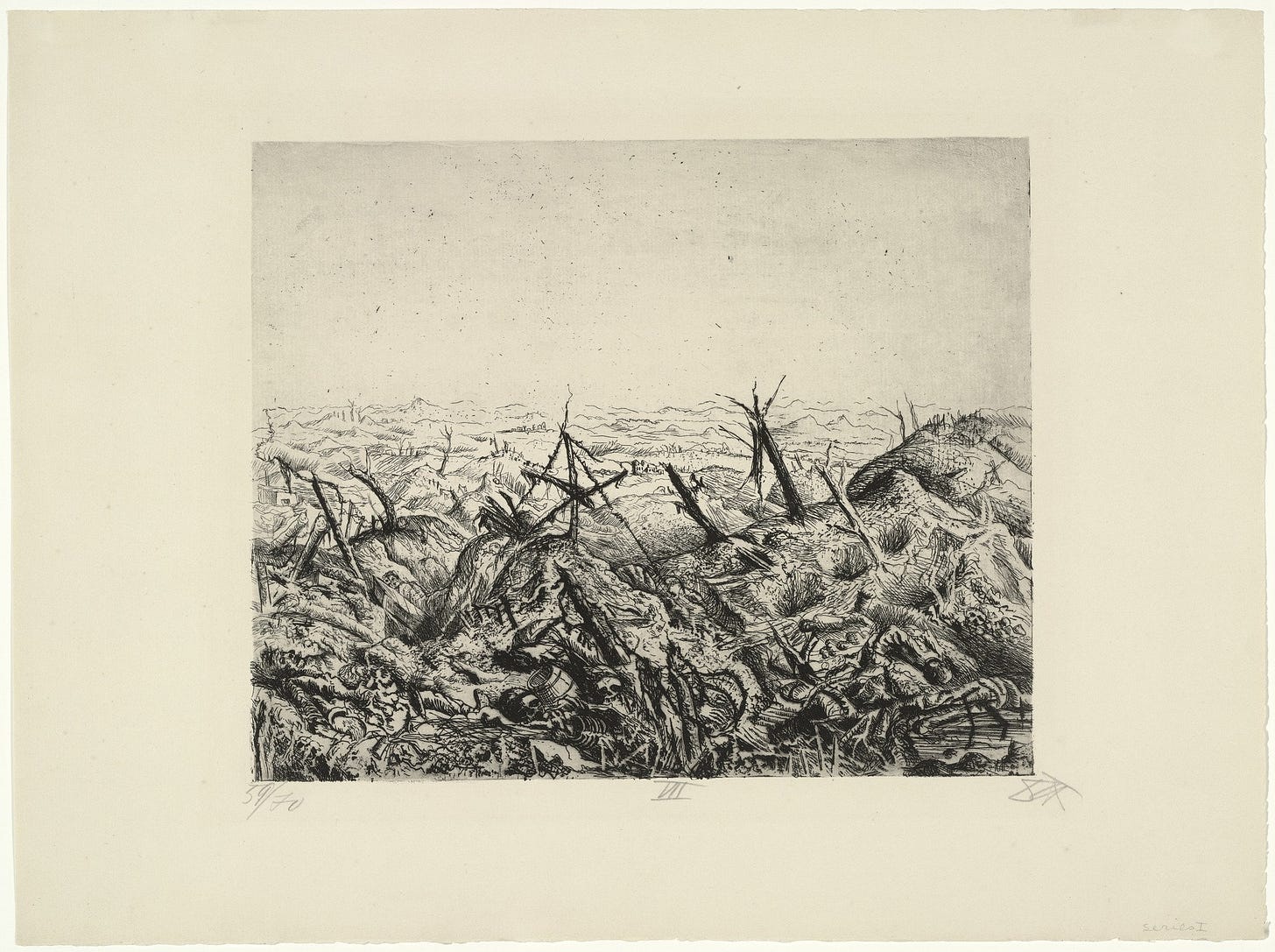

Now the battle of position begins, where the increasing gravity of the war is indicated by the repetition in army reports over several years of names of the same villages, the same forests, the same rivers, as a sign that for all sides the gains are decreasing in proportion to the severity of losses. The gravity of the battlefield becomes so great that the last efforts of the great empires are spent in conquering swaths of devastated land, shattered patches of forest, and destroyed villages.

The vitality of the great armies which held the states in readiness is far from exhausted, on the contrary, it is multiplying, but it is like a weight held up by a counterbalance. The point of balance is no man’s land, a narrow strip of land, often less than a hundred metres wide, which nevertheless becomes insurmountable. And when the attackers, dressed in the colour of the field or ground, manage to cross it after increasingly careful preparation that defies all the laws of military economy, the depths of the enemy open up before them, an environment of resilient endurance that weighs down every step with a lead weight. In a few hours, a few days at the latest, this isolated strip of land, dotted with iron wires, is once again open to their gaze. The scales tremble for shorter and shorter periods of time, their measure losing more and more decisive significance, no matter with what load one may load their plates.

The weights used are the masses of material that the technical operations of the great industrialised nations fabricate with ever more strenuous effort. The sense of strategy seems to have been cheapened; one wants to crush the opponent because one can no longer defeat him in the open field.

Thus the image of a material battle emerges, the image of a tremendous display of technical energies in which the effect can never go beyond a tactical success. In these battles, the intensification of fire assumes unimaginable proportions. Artillery was transformed into siege spaces, with ever-increasing numbers and weights of guns whose effectiveness was enhanced not only by increasing ammunition consumption, but also by the fact that they are directed at stationary, limited targets. This led to the emergence of the new concepts of barrage, cold fire and barrage fire. The use of gas further increases the density of fire, as gas penetrates even dead zones and shelters inaccessible to shell bombardment.

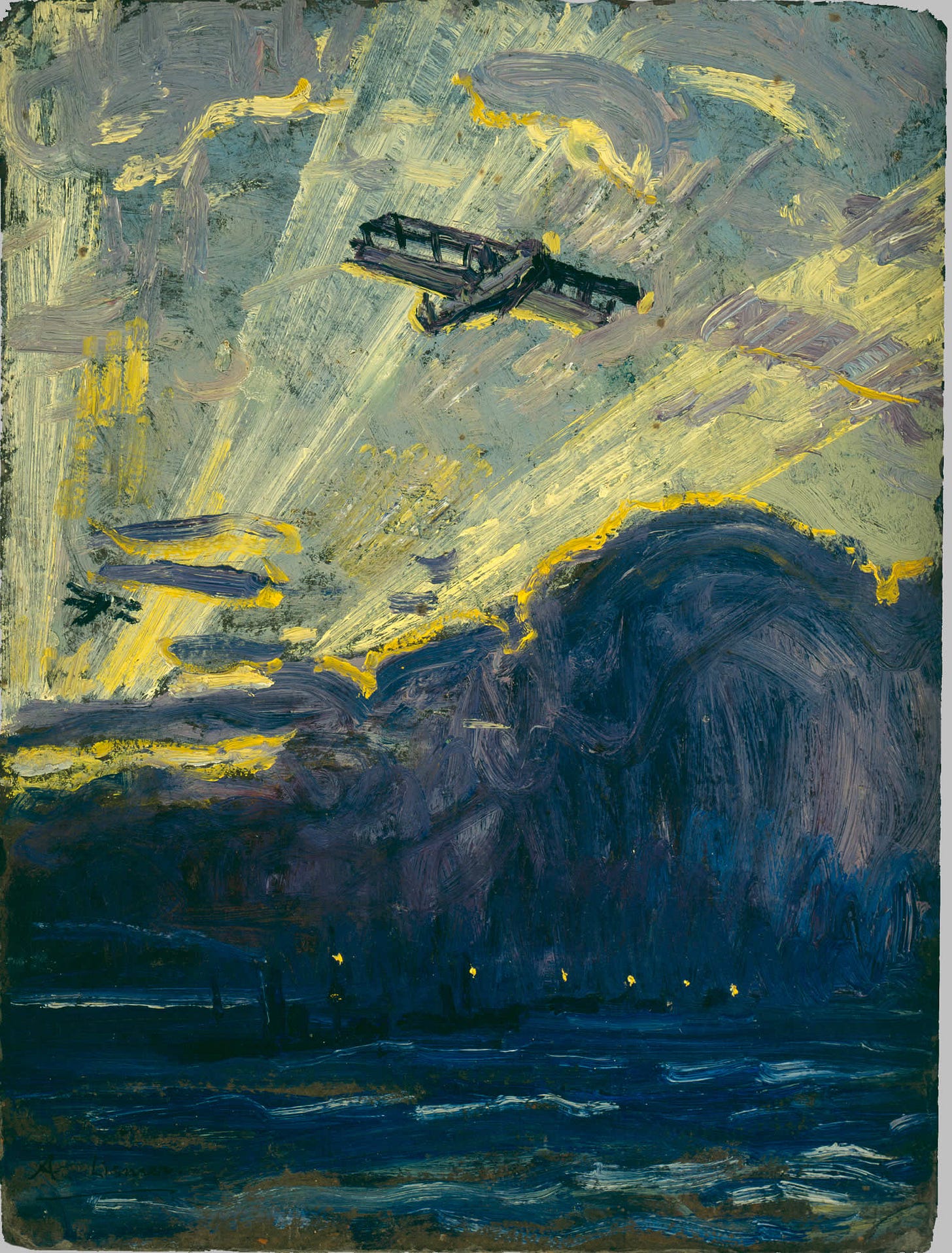

Infantry firepower increases in the same proportion. They, too, are increasingly able to develop an artillery effect; hand grenades, infantry guns, mine launchers, grenade launchers and trench mortars appear. The effect of purely infantry defence was enhanced not only by the multiplication of machine gun companies, but also by the fact that infantry groups themselves were equipped with light machine guns, and later with machine pistols. On the other hand, the third main weapon, the cavalry, the classic weapon of advance and pursuit, loses importance, it enters into the work of other branches of arms, or it seeks out theatres of lower rank. The fact that many cavalry officers moved into the air force shows that the need for movement had taken on new forms appropriate to the times and that the struggle for supremacy had to be conducted by other means.

It took a long time to realise that the calculations of stacking material masses against each other were insoluble. The years 1915, 1916, and 1917 were filled with increasingly costly trials of this kind. The work of industry was to produce fire on the front and increasingly dense barrages across that front. It is true that on this frontline the measure of movement seems to depend on the measure of fire. When troops advance, they do so under blazing helmets and whistles, which they can leave behind no more than a diver can exit his suit within the element of deadly pressure. Nevertheless, when this is to be enforced, disasters take place. General Nivelle's offensive, based on the urge to move at all costs, brought the French army to the brink of destruction. The great battles of Verdun, the Somme, and Flanders, after meagre initial successes, after narrow offensives, after protrusions, after the capture of several forts, after the slow and sacrificial devouring of the front, fall in exhaustion. Movement seeks out ever more limited objectives, the outskirts of villages, sections of trench, and isolated points on the ground; it occurs after increasingly long pauses, as if fire acts as chloroform. Fire has the particular property of supporting the defence far more than the attack. Thus, in terrain where defenders have nearly been eliminated a few machine guns can break up attacks prepared by a thousand guns.

Following the attempts to enter the open field the scene of free movement, behind “rolling fire” on extended positions, a picture emerges of a battle that is as monotonous as it is strange, and in which only fire remains of the two elements of combat. One renounces marching, he “shoots the enemy who is out of position.” It is for this task that technical means are placed in service, in their specificity and in their interaction. At this stage the infantry is a kind of executive arm of the artillery. The great slogans indicate that the belief in a strategic end to the war has been lost. Prolonging the war becomes a system: one must “hold out”, bleed the enemy white, weaken him within the strongholds of the will by starving him, or accelerating the consumption of his moral reserves.

Thoughts that are extraordinarily difficult to grasp at the moment of action, and under the compulsion of action, seem most obvious after the events have taken place. Therefore, today it strikes us as absurd that a warrior will rely almost exclusively on the possession of a gigantic technical apparatus to increase fire, while movement in battle, on the whole, is still anticipated as primal energy, the muscular power of men and horses. Of course, this is not the case with all the elements that man has placed at his disposal for movement. For example, at airports weapons are transported by planes that can reach enemy capitals within a few hours. But these new machines, however quickly the spirit may have developed them through the course of the war, are not yet numerous enough in quantity, not yet formidable enough in type to be decisive in their own respect. They can be used for surveillance, for harassment, for increasingly subtle destruction - but the value of these operations is tactical in nature, an air strategy has not yet been created. It is not yet possible to liberate the great war, which lies below in strife, by taking it into the air. Air strikes are not yet a means of forcing submission.

Similarly, movement at sea has long been produced by machines. Even though the large fleets have been at anchor for a long time, it is not a question of whether they can move or not, but whether they should move or not. Their movement is a matter of will, not possibility. Thus, it strikes us that their immobility affects the morality of war, where violation of the will coincides with violation of the spirit, more acutely than in any other area of human endeavour.

The fact that the mobile war machine does not appear until relatively late on land, the oldest element of battle, is connected with one of the errors in thinking that is characteristic of human history. After all, it is just as certain a mistake of thought to want to increase fire by increasing it in quantity as it is a mistake in business to expect success from competition based solely on price. When prices reach their limit, competition moves into the realm of quality. Thus, when the production of fire by machines reached its last capacity, machines had to be invented to produce movement. Such machines, independent of rail tracks, had been available to man’s intelligence for some time – it was only a question of giving them their special form in combat.

There is nothing new under the sun – a force like the first rolling of tanks in material battles has taken place many times before, so long as there have been wars. The attempt to destroy fixed formations, tested by time, with horses, chariots, war formations, elephants, wedge columns, is repeated here in the machine age, by mechanical means. It cannot change anything in the strategic laws, which in a sense are the a priori forms of the vision of war, but it is born out of a desire to place these laws at the disposal of a new executive power adapted to the times. The moment, therefore, when the first motorised tanks appeared in front of German positions on the Somme is a historical moment of the first order. These machines still resemble children’s toys that break easily – but the history of invention is rich in toys of this kind.

Nor can it be said that the tank developed into a weapon that decided the outcome of the war. Its full power did not come to fruition, and so on its ground the deadly competition between human and mechanical power hinted at more beneath the surface – a competition in which the machine still retained the longest breath in every field in which it appeared.

Just as the tank could not achieve its technical perfection in a short period of time, so the nature of its use and the limitation of its tasks have not yet been determined. It is only a means, one of fighting in a technological space, the laws of which it does not define but imposes, and to which it owes its emergence. It is an expression of the new military age, just as the machine itself is only an expression of the new age of reason. This is why the tank does not create an image of the technological battle, but is a phenomenon within its framework. How this frame is created by the efficacy of the new thinking is as difficult to describe as it is to express a new image of the metropolis. Battle not only relies on the machine more and more, but also imbues it with the spirit that machines create. This spirit is already expressed on a small scale in the shock troop, in the fantastic piecework of human attack, and on a larger scale it is manifested in the German offensive of spring 1918, which is important not so much for its means as for its inexorable precision – a driving process in which the will of the general, which has become abstract, expresses itself.

In this light the World War appears as a gigantic fragment to which each of the newly industrialised countries contributed. Its fragmentary nature is explained by the fact that technology destroyed the traditional forms of warfare, yet could only suggest a new image of war without being able to realise it. In this process, the World War reflects our life in general – and here too the spirit of technology was able to destroy the old bonds, but has not yet emerged from the experimental stage to build a new order of life by its own means.