From Die Kommenden Titanen

Published in 2002

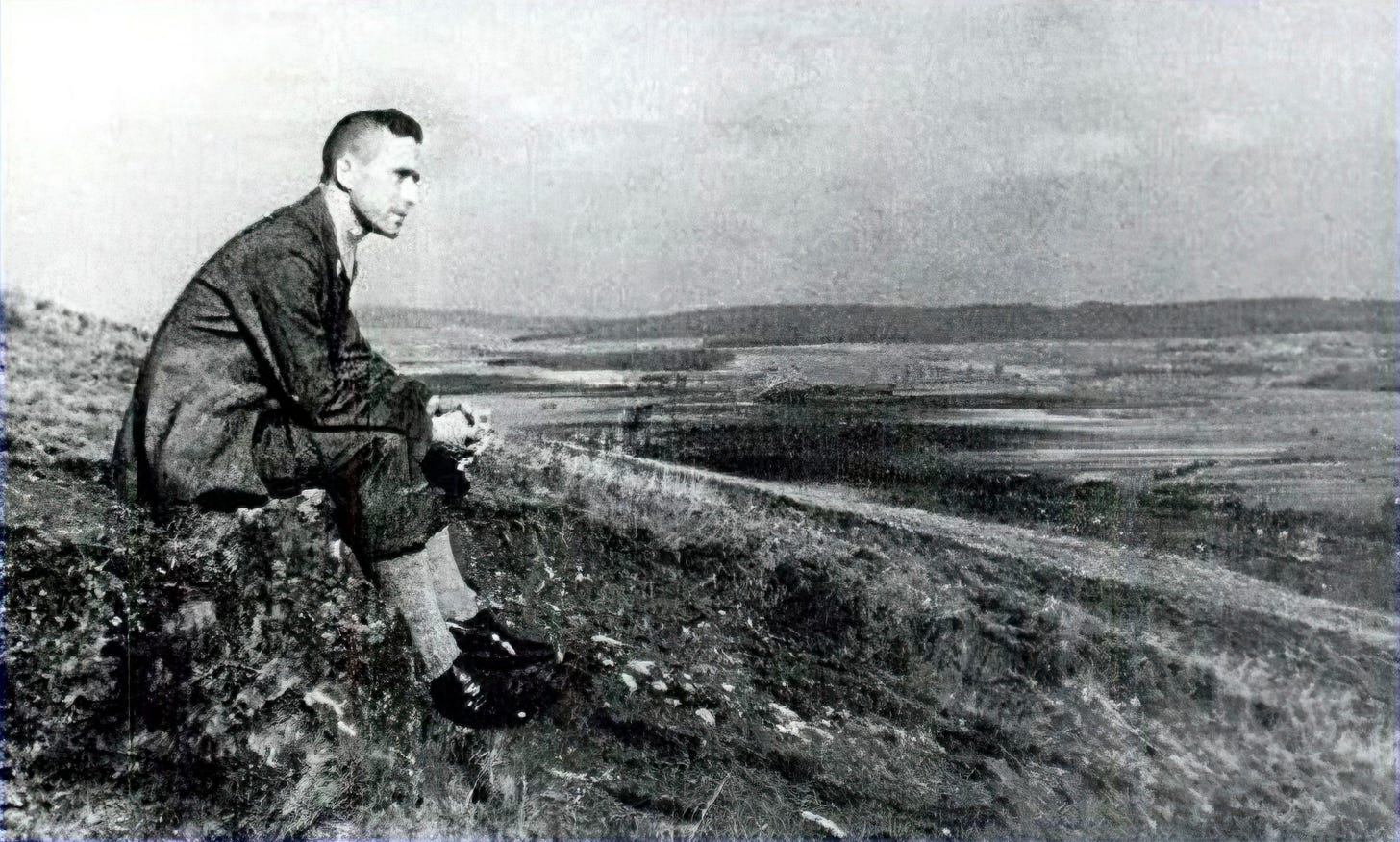

On 29 March 1995 Ernst Jünger turned one hundred years old. For some time he has lived in seclusion in Wilflingen, Upper Swabia, avoiding the curiosity of journalists, admirers, readers and scholars of his work. The only thread linking him to a very few intimates is a secret telephone number.

For his centenary, celebrations and festivities had been prepared all over the world. Helmut Kohl, François Mitterrand and Felipe Gonzalez, who had already visited him in Wilflingen in the past, intended to award him their countries’ highest honours. But Jünger had discreetly let it be known that he was not going anywhere. The upheaval that the jubilee threatened to cause in his rhythm of life and work worried him so much that he would have preferred to escape to a remote atoll in the South Seas and wait until the centenary celebrations were over. He told the press and television stations around the world who asked to be received that he would not give interviews.

We were lucky enough to be the exception to the rule. The reason for the privilege that Jünger granted us is the good relationship that was established with him.

Our first meeting took place years ago, at the time of the preparation of Across the Line, the volume in which the texts of his controversy with Heidegger on nihilism, of which only separate editions existed in Germany, were collected for the first time. We wanted to discuss some of the details of the text directly with him, to recall the circumstances of its writing and to reconstruct the relationship with Heidegger.

The reception was immediately very jovial. We enjoyed in advance the consideration Jünger always had for his translators: ‘With translators I have had a particular good fortune. That the author and the translator become friends is natural. Their meeting leads to a spiritual eros and agony, it leads to penetrating the linguistic exposition to its very depths. To live up to it, to master it with cunning, strategic moves, surprises, until consonance becomes harmony - in this way a new work can be born, in which both take part. Thus in a successful translation the author sees himself in a new dimension’. The conversation soon enough moved on from Across the Line to another topic: the ‘discovery’ of an unpublished work by the elder Schopenhauer in which this unrepentant metaphysical pessimist, now at the end of his life, redeems himself from his sin during a ‘night troubled by doubt and uncertainty’. Jünger was attracted by this text, and mentions it in Die Schere. In his diaries he then recalls our first meeting and the reason why this conversation about Schopenhauer struck him. A series of visits to Wilflingen followed, and then a meeting in July 1995 at the Escorial, where Jünger and some friends stayed for a whole week to receive an honorary degree from the Universidad Complutense de Madrid. The conversations we present here are the result of a series of visits to the Escorial.

The conversations we present here took place during three meetings in Wilflingen, specially organised for the production of this book-interview. The first took place on 9 March 1995, on the eve of his hundredth birthday, and part of the conversation was then published in the “Repubblica” of 12 March. On that occasion, in the afternoon, we also made, together with Silvia Ronchey, Giuseppe Scaraffia and Marcello Staglieno, the documentary for television Ernst Jünger’s Hundert Jahre, broadcast by RAI on the occasion of the centenary. The second and third meetings, agreed upon during the summer of that year, took place the following autumn, on 4 and 5 October. We spent the night near the castle in nearby Sigmaringen and spent two intense days with Jünger and his wife Liselotte in their house opposite the Stauffenberg castle in Wilflingen, simply letting this extraordinary witness of the twentieth century, who has now passed his old age and entered the age of the patriarchs, tell us everything that emerged from his memories and what he still plans to do with “what remains of time”. The conversations thus developed according to the free and unpredictable course of the association, without being caged in a series of previously prepared questions. This is how we have left them, and we are publishing them now, in their immediate freshness, as testimony to the extraordinary vitality and lucidity of this great solitary man.

ANTONIO GNOLI, FRANCO VOLPI

FIRST CONVERSATION

Since 1950, Jünger has lived in Wilflingen, a village in Upper Swabia a few kilometres from the Black Forest and Sigmaringen, the small town dominated by a castle that was once the residence of Marshal Pétain. These are the places where Céline set his novel From One Castle to Another, evoking the tragedy that buried the collaborationists. It is difficult to forgive a writer certain historical judgements. It happened to Céline. And it happened to Jünger, who was repeatedly subjected to demolishing attacks. Sometimes the past is used as a magnifying glass to investigate the moral details of a man’s life. But in the details, one risks losing sight of the general plot of an existence, which is often vague, contradictory and surprising.

Not surprising, however, is the calm that envelops Wilflingen. There is a quietness that repels any urban intrusion: few houses, few cars, few people. An invisible order governs the silence in which Jünger has retreated for over forty years. For his 100th birthday, the Christian-democratic Wilflingen municipality has decided to give him an unusual gift: from that day on, electricity, water and gas will be provided free of charge. This is the way in which the small community of about four hundred souls wanted to show him their affection. Other celebrations are in the pipeline: honours will pour in from Spain, France and Italy, together with Germany, the countries in which his thought is most deeply rooted and attention to his life and writings is most evident. In past years, the great of Europe have visited him. Like a head of state, or rather like a symbol of a Europe that perhaps no longer exists, and of which Jünger is in some ways the ultimate witness.

Today, the former aesthete and flâneur, that German army officer so at ease during the occupation in the versatile Parisian worldliness, has given way to a curious patriarch who seems to observe the world with the gaze of an ironic entomologist grappling with a new species of insect. After all, among the many activities that marked his life - he was a diarist, essayist, novelist, soldier in the two wars, traveller - there was also that of a scientist bent over the world of nature to study and catalogue certain species of beetles. The house in which he lives, a two-storey building overlooking the castle of the Stauffenberg counts, bears witness to this. Here, in a humble Biedermeier setting, Jünger exhibited his collections of beetles mixed with collections of hourglasses, fossils, shells and war relics. It is a world of taxonomies of the past that he shares with Liselotte, the woman he married in the early 1960s after the death of his first wife.

It is she who receives us courteously and escorts us up the stairs to the first floor, where Jünger “greets us with an indefinite smile. He is small, thin, harmonious. Standing in the living room, he extends his hand to greet us. In a succession of gestures, his fingers first indicate where we should sit, then graze his white hair, and finally fall back along his hip in a stiff arm movement that seems to recall his military past.

You will be a hundred years old in a few days, and you are considered the extraordinary interpreter of an adventurous and eclectic century, as eclectic and adventurous as your life and work have been. What is your impression of having lived through it all?

I was born in 1895, the same year in which Röntgen discovered X-rays and the Dreyfus Affair broke out. Röntgen’s discovery gave birth to the technical century. For the first time, it is possible to look inside matter and observe what the microscope could not see. Without Röntgen we would not have had the development of atomic research, we would not have achieved splitting, nor would we have been able to think about atomic fission. As you can see, a small, great scientific gesture is at the origin of this century’s modernity.

As for Dreyfus, the affair that broke out over his case can be said to have left a decisive mark on the history of democracy as a victory of critical public opinion over conservative forces.

The year in which I was born, therefore, anticipates in technical and political terms what was to come in the twentieth century.

In what way did these two events mark you, if you can use that expression?

Let’s say that they were not so much motives I was interested in as the very air I breathed. I remember that in conversations at the dinner table with my parents, at the beginning of the new century, these two topics were the central topics. We would talk about the Dreyfus Affair and we would discuss, because my father was a chemist, new scientific discoveries. It was inevitable that, even as a child, I would look carefully at what was happening, sensing and foreseeing what would happen later. At that time there was great optimism: it was said that this would be the century of Great Progress. And it was not so much the First World War that shattered that confidence as the Second. The essential change in our century only really took place from the middle of it, from 1945 onwards.

His dating is unusual. It is usually assumed that distrust of the idea of progress manifested itself at the beginning of the 1920s, immediately after the First World War. And it is no coincidence that Germany, which had been defeated in the war, became a sort of spiritual guide that developed a very pessimistic critique of the values of progress...

On a philosophical and literary level, in the great visions of history and in the prognoses on the future of civilisation, the motif of Kulturpessimismus emerged even earlier, and had its strongest and clearest expression with Spengler. From the idea of a linear progress of history, which implies an ever-increasing development, he returned to a cyclical configuration in which development does not continue indefinitely, but is a phase of life between birth and death.

What this view of history and his Kulturpessimismus produced in us, however, was not a twilight attitude. We young people could not afford a décadence like the French generation of Huysmans had allowed itself at the end of the 19th century. Tiredness in the evening is healthy, but before midday it is worrying. It was also a question of character. The apocalyptic visions triggered by the passage of Halley’s Comet in 1910, or even more so the sinking of the Titanic two years later, instead of having a depressing effect, fired our imagination. Our attitude was that of someone who wanted to recognise the new reality of technology and work with a disenchanted eye and take part in it without nostalgic regrets or apocalyptic projections. If anything, it was a matter of finding, in myth or history, a power that would counterbalance pessimism. As Nietzsche had said in Ecce Homo: “... I am a décadent: but I am also its antithesis”. In the fire of the sunset announced by Spengler, what I saw was the rise in all its power of the figure of the Worker. It was the Second World War that brought us down into the depths of the maelstrom, into the vortex of nihilism.

But what is your idea of progress?

For me it is an anthropomorphism with which modern man has tried to read history. It is a substitute for the idea of the ‘spirit of the world’. We must distance ourselves from it and look at the universe and its history from the point of view of the principle of the conservation of energy. The power of the cosmos always remains the same, there is no progress or regression or acceleration or deceleration that can change it. What changes are only the figures, the forms that history, indeed the earth, ceaselessly produces from its depths. The problem I see arising here is another: can we hold man, this sovereign apparition in the history of the universe, responsible for its evolution?

We mentioned war, which is a motif addressed above all in your early work. What does it feel like to think back on that theme today?

First of all, a clarification: for me, the real great reason for interest was technology, whose power was impressively manifested in the 1914-18 World War, the first ‘material war’. It was a profoundly different conflict from all those that had gone before, because the clash was not just between armies, but between industrial powers. It was against this backdrop that my vision of war took the form of heroic activism. Of course, it was not simply militarism, because even then, I always conceived of my life as the life of a reader before that of a soldier.

In what sense?

In the sense that it was mainly the reading of certain books that gave me reasons for action. When I thought I could get those motives from reality, I was deeply disappointed. I mean that heroism for me was born more from a literary experience than from a real and concrete possibility of life.

But what connection was there between the two levels, between literature and life?

Literary reality, unlike concrete life, was inevitably destined to be dissolved by the technological transformation of the world. Hence my attempt to elevate literature to a life experience before Marx’s prediction that it would no longer be possible to conceive an Iliad after the invention of gunpowder came true. Which is to understand what happens with the entry of technology.

For you, is technique such an important watershed that it is decisive in the separation of worlds, even literary ones, that are different?

Technique is the magical dance that the contemporary world dances. We can only participate in its vibrations and oscillations if we understand technique. Otherwise we are excluded from the game.

We will touch on this point. In the meantime, to highlight some biographical aspects, it must be said that you were considered a hero of the Great War, you were repeatedly wounded and then awarded the highest honour, the “Ordre pour le Mérite”...

I was drawn to heroism by reading Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso. It was those words, those rhymes read during the breaks between one battle and another that motivated me. It was not the rhetoric and ideology of war that had developed after our victory in the Franco-Prussian war of 1870-71, the importance of which our fathers’ generation had greatly overestimated, when in fact it had been a small war. This overestimation manifested itself in particular in the ideological antithesis between the noble Prussian spirit and the English mercantile spirit, fomented by Wilhelm II who could not stand his cross-channel kinship. It could be added that Germany lacked a Shakespeare who could represent its events. After all, how could one expect a Shakespeare if the characters and actors of that phase of German history were not great enough to deserve it?

Is it always true that great works need great static events?

Great events are always literary. History, with its facts, is an overflowing storehouse from which everyone can take what they want.

What you say only confirms how important a certain aesthetic vision of life has been in your choices, rather than ethics. How do you explain this inclination?

To see the relationship between ethics and aesthetics simply as an antithesis is not enough for me. On the contrary, it is misleading. I would therefore say that ethics and aesthetics meet and touch each other at least in one point: what is truly beautiful cannot but be ethical, and what is truly ethical cannot but be beautiful.

But this is style after all. Is your vision of the world really one of style?

I hope so. And that is why I have never descended and will never descend into controversy. I find it in very poor taste. Never stoop below your own level.

Do you think it is still possible to preserve style, this delicate and aristocratic gesture, in a world that tends towards depersonalisation and manipulation of the individual?

I would define ours as a society of massified individuals, which therefore needs very restricted elites, destined to perform a very important function. On this point, I would adhere to the Heraclitean sentence that says: “ To me, one is ten thousand”. This number should be raised to a power today.

In the sense that the elites should be enlarged or restricted further?

In the sense that the more massification increases, the greater the value and spiritual strength of those few who are able to escape it.

We are used to thinking of elites in more sociological than spiritual terms. What definition would you give of them?

The sociological definition of elite is already an indication of the corruption of the concept. A warning, for me, to no longer trust even the elites, but now only the great loners.

You mentioned earlier your choice to never get into controversy. Yet you have often been involved in controversy. Especially because of your past in the German army, a past that more than one critic reproaches you for the indulgence with which you tolerated the Nazi regime. There is also an episode on which we would like to hear your version. When your novel On the Marble Cliffs came out, in which the idea of tyrannicide was mooted, you took risks. Goebbels and Goering wanted your head, but Hitler said: “Jünger is not to be touched.”

Controversy does not have the same depth as ideas. It is not a question of living up to them by responding in tone. Because there is no tone, only noise. As for Hitler, that’s how it was. It was not a week after On the Marble Cliffs came out in the bookshops that the Reichsleiter of Hanover, a certain Bouhler, complained in Berlin that he thought the book incited a conspiracy. Hitler, who was an admirer of my World War I diaries, ruled that they should leave me alone. On more than one occasion he had made signs of friendship and expressed interest in me. But I did not let myself be flattered by those offers. It would have been too easy to exploit them for personal gain. It would not have taken much to do as Goering did. I would also like to add, even though I think an author should respect the rule of never talking about his books, that in the case of Marble Cliffs the political effect was secondary for me. Some friends have reproached me for downplaying this effect, which for many was the most important one. However, I prefer to draw attention to the fact that in that case I placed myself on another level. After all, it is clear that if mine had become a political stance, I might have found companions and followers, but I would have fallen at the same level as Hitler. I was his opponent, but not a political opponent. I was simply in another dimension.

Did you ever meet him personally?

No, I never met him. When he was still an anonymous leader of a small group like Niekisch’s National Bolsheviks - and I was still living in Leipzig at that time - one day, it must have been in 1926, he had Hess announce himself to me, but I didn’t have time to receive him. Besides, I was convinced that he was one of the many insignificant sectarians who were circulating at that time. Thank God that meeting did not take place. If it had happened, and Hitler had perhaps put his hand on my shoulder while someone was immortalising us, I imagine that the photograph would have gone around the world. Fortunately, things turned out differently.

Hannah Arendt famously said that you were always on the side of the Resistance despite the fact that your books had influenced the Nazi elite.

I am aware of that recognition, which of course flatters me. But personally, having seen and experienced what happened before and after, I feel a certain allergy to the indiscriminate use of the word ‘resistance’. Not to mention that spiritual resistance is not enough. One has to fight back.

Are you telling us that you have some regrets for what you did not do?

I can see that in the end it is the way one opposes a heinous regime that counts.

Have you ever met Arendt?

No, I never met her; it was Heidegger who often spoke to me about her.

You shared a certain destiny with Heidegger and Carl Schmitt. What is your memory of them?

I have not only a literary but also a personal, private memory. I was a friend of both. I met Heidegger several times and visited him in his chalet in Todtnauberg. One must now be able to make an objective judgement of him. I mean that at this point it is a question of evaluating the thinker for his speculative power and not for his political opinions. The same applies to an artist or a poet. For example, I greatly admire Heinrich Heine as a poet, while I do not share his political convictions at all: between the two perspectives, it is preferable to adopt the favourable one.

With Carl Schmitt I had an even closer, very personal relationship. Among other things, he was godfather to my son Alexander, whose birthday it would be today.

We shall return to this. But speaking of politics, in Italy there is a heated debate about ‘right’ and ‘left’. What do you think of these two categories?

They are now organic categories, like parts of the body. Think of the hands, for example: both are indispensable. It is obvious that each exists in function of the other. From this point of view, therefore, the ‘right’ and the ‘left’ are equally necessary. What has been clear to me since the convulsions of the Weimar Republic is that the traditional spatial depiction of the political significance of these two categories no longer holds, according to the image of a parliament in which the right sits on one side and the left on the other. And this is even more true today, in the age of technology and mass communication. Personally, however, I consider myself beyond this scheme, which has filled shelves with ideology.

Speaking of technology and mass communication, apart from the invention of X-rays, your year of birth was also the year of the invention of cinema. What is your idea of this art, so popular in our century?

I like to imagine cinema as something that concerns the relationship between technique and magic. A relationship that is still to be explored, also from the point of view of the public. I wonder if cinema has replaced, even partially, the novel, and what effects this replacement has produced. Even if the cinema-going public, precisely because it is vast and anonymous, does not exactly coincide with the reading public.

You mentioned magic in relation to technique: that’s a good definition of cinema.

There is often something amazing about technique. It’s funny, but sometimes when I’m talking to someone on the phone, I still have the impression that I’m performing not only an act made possible by technique, but also something magical. It applies to cinema, to the telephone, but also to other things. We can record our conversation, film it, and then bring it back to life in a hundred years time, perhaps from a different perspective. Filming gives us the opportunity to resurrect missing people whose memory, physical presence, voice, gesture have been lost. I believe that this effect, which I call magical, is destined to emerge in an even more impressive way. There is already talk of virtual reality, of the fourth dimension. Thought itself is becoming digitised.

And what about television?

It too has a magical significance. And this sorcery aspect is not due, let us be clear, to the attitude of a primitive in front of a surprising and unknown event. Through television we can bring to life a reality that is not present before us. What I expect is that soon we will be able to have television images in three dimensions. Its magical character would be enhanced.

So much for the future. So how do you imagine the next century?

I don’t have a too happy or positive idea. To use an image, I would like to quote Hölderlin, who wrote in Bread and Wine that the age of the Titans will come. In this coming age, the poet will have to go into hibernation. Actions will be more important than the poetry that sings them and the thought that reflects them. It will be a very favourable epoch for technique, but unfavourable for the spirit and culture.

I especially appreciate this interview for its rare acknowledgment on the part of Jünger that he indeed had regrets for things he didn’t do — a recognition that while the Forest-Goer and the Anarch are two figures of the same essence, the former is its fuller expression.

Would you happen to be able to point me to further explanation or discussion of the unpublished text by Schopenhauer mentioned in the prologue to this interview?

By the way, as a reader who loves both On the Marble Cliffs and Eumeswil, I very much hope that someday soon Heliopolis is Englished, as I understand that is the second in something of a trilogy formed by those works.