The Machine - Ernst Jünger

First published in Die Standarte, December 13th 1925.

This is not an original translation by us, however it is an essential essay to understand Ernst Jünger’s later work on technology. Corrections have been made to improve the quality of the text.

The world we were born into appears to us as something self-evident. From the very moment of our birth we are surrounded by a multitude of things, with the first inklings of consciousness we learn to more clearly define them from the perceiving self. We could not talk yet and did not know what motion is, but the noise of trains that rushed on the rails through forests and fields was already something familiar to us. If we were to grow up in some cabin among the virgin forests of South America we would become acquainted with motion, observing the treetops waving in the wind, flying birds, and the flight of an arrow. Village, colourful birds, and arrows would be something natural to us. But from our mother’s arms we observed huge iron wagons and complicated steel mechanisms, not understanding them in the slightest. This truth was discovered in the history of thought a long time ago: first we perceive objects and only later subject the variety of experience to strict classification. We should sometimes remind ourselves of this truth, in order to see just how much we are connected to our era and our surroundings. We assume that we can conquer both with thought, but in reality thought is but their function.

Today, sitting comfortably in the seat of a restaurant wagon with a newspaper in our hands, we pay no mind to the landscapes passing us by. Moreover we will not be surprised with the towns and villages passing us by in the window. We are well familiar with them from our early childhood, this is our world! Yet, let us at least once try and see them with different eyes, for instance with the eyes of a man from another era, when fortresses, monastic buildings, and cathedrals towered above.

Forests and fields carved up with the shiny canvas of a railroad were not always as they appear today. These are not just forests and fields as such, these are forests and fields that belong to our time and place. Neat rows of beeches and firs remind us of soldiers on parade. Rye and wheat form strips on a rectangular field as if measured with a ruler. All this was done by a machine. Individual grains, one by one in a strict line. Just some thirty years ago fields looked completely different.

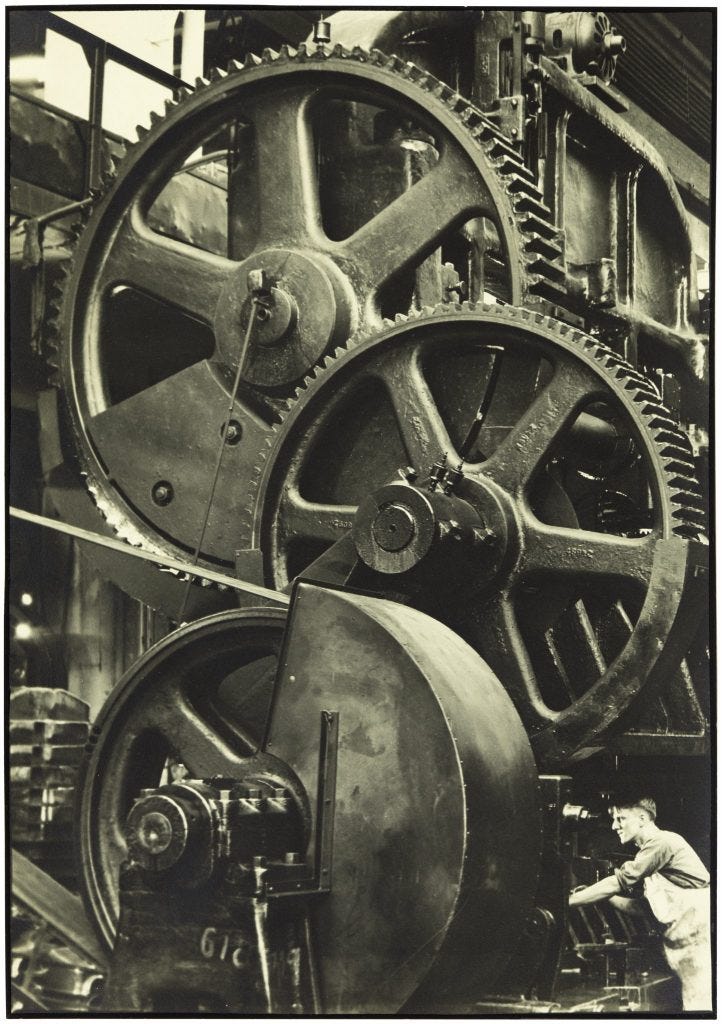

And thus we arrive into a big city. Masts of traffic lights appear, bridges on narrow iron piers. We rush by marshalling yards, conglomerations of levers and wire, strict factory silhouettes in the windows of which we can see flywheels and shiny bulbs. And the closer we approach the center the more tightly we are surrounded by a magical garden with its peculiar technological plants.

We leave the train at one of the gigantic stations (hints of the modern imperialism style in their architecture) and go to the streets. Night has already descended. We dive into a colourful sea of light, bright signs glide on building walls, fire wheels spin around towers. Caravans of machines rush through wide squares and narrow shafts of streets; rumbling, hissing, honking – they are like screams of dangerous animals. Yet we calmly and indifferently walk through all this chaos beneath the artificial sky of arc

lamps, we are surrounded by a magical landscape that surpasses any fantasies of “One Thousand and One Nights”.

Here we feel at home. It would not be a mistake to say that we live in a fairy tale world. Everything comes and goes, and it may seem that when our world sinks into nothingness, our descendants will tell legends of us, legends about evil and mighty wizards. Yes, we have created great and wondrous things and have the right to be proud of them. For there are such moments when we truly are proud of that which is called progress. Let us remember the intoxicating joy that overwhelms the modern man at the sight of his own creations burning gigantic amounts of energy in the sky above the metropolises. Let us also remember the feeling of emptiness on weekends when this gigantic machine is made to stop. Then it appears to us as though the masses of leisurely shuffling people in the streets have lost their true meaning, and the praise of holidays that we have inherited from more pious ancestors almost looks like sin. We are ready to completely transform life into energy.

However there is still a deep fear hidden within us before this mechanical apparatus, this witch’s broom that it seems we forced to move, yet as if the sorcerer’s apprentice forgot other enchantments and became confused. Fear consciously manifests itself when technology is seen as the result of rational thought, believing that the spiritual world had irrevocably perished and in its place appeared the cult of material gain. It is particularly vivid in the new generation that had survived the war, which instinctually chooses common blood and seeks to avoid any rationalistic worldview.

Truly, the machine has taken much from us. It made our life more energetic but it also took away its lustre. Taking the whole from us it turned us into specialists. We thought we would be able to make it work for us as an iron servant, but instead we were ground up by its wheels. When Keyserling in his “Travel-journal of a Philosopher” stated that in the end it was a great delusion that we achieve everything with machines, leaving ourselves only the function of control. With every new machine the strain on us grows – it is enough to look at statistics.

However, it is important to understand that the motion of machines is of a compulsory character. It runs over whoever stands in its way, becoming a means of destruction. Any protests will crash against its steel shell, like the protest of English factory workers who revolted against the use of first steam machines. One cannot deal with machines with bare hands – this is a lesson we learned from fiery battles of military technology. And here is something else that is important to remember: the machine is not at fault for the world losing its deeper dimension – which is exactly the reproach used against it by the false desire to “internalize”. Only man himself is at fault, if one can speak at all about faults when it comes to such matters. Today the machine is an instrument of a particular, singular man, and their massive unification becomes the instrument of the nation. And through the machine the spirit can do anything it wants, just as with any other instrument.

Nietzsche’s renaissance landscape had no place for the machine. But he also taught us that life is not only a struggle for a mere pitiful existence, that it can seek higher and more serious goals. Our task is to apply this teaching to the machine. We have no right to view it as a mere means of production, the satisfaction of material wants, because it can satisfy needs of a higher order. And that is why we must free it from the shadows of intellect and place it in the service of the will and blood. That which in the language of the intellect is called means of progress, in the language of blood is called means of power.

Intellect creates the instrument, but the will of blood directs and utilizes it. Machines are used to fill entire countries with cheap products and to create technological trinkets. Machines are used by cultured nations to create tanks and offensive weapons for themselves and it is clear that this does not stop at steel plates and gun barrels.

As in war, so in peacetime modern nationalism is incapable of operating without machines. Battles of the Teutoburg Forest, which were wages with clubs and flails, are long behind us. Now, if a country does not possess the necessary technological arsenal that allows for sending trains, print slogans, and generally imposing any will onto our time and place, it is doomed to failure.

There were people who during the war, believing in the supremacy of spirit over matter, had sent soldiers into battle without modern weapons. Such mistakes were paid for dearly. Of course the spirit possesses supremacy over military technology, but this does not mean that they should be set against each other directly. The supremacy of the spirit presents itself in the ability to control technology according to one’s will. In peace time we also must seek to equip the nation with the newest technology. During certain times people express themselves with bombings and gas attacks, whereas in other times the cinema, radio, and press become such a means of expression. Here we have a vast field to work with.

But one cannot conquer this space unless one first conquers the modern factory worker. We must convince him of the necessity of finding an exit from this dead end of marxist and capitalist presets, which, being connected exclusively to issues of production, have led to the industrial war and the Battle of the Somme.

We must find a new way to freedom. We must convince him that our values have no monetary equivalent, we do not engage in distributing gain but are solving a question of blood and power. To us he is not some unskilled labourer but a comrade with equal rights. The worker has been easily bought with promises time and again. But what Marxism offered him in a purely material sense, nationalism can provide and much more.

The factory worker is the first and strongest factor in the rise of modern nationalism which presents in itself a new European phenomenon.