First printed in: “Der Scheinwerfer”, September 1930

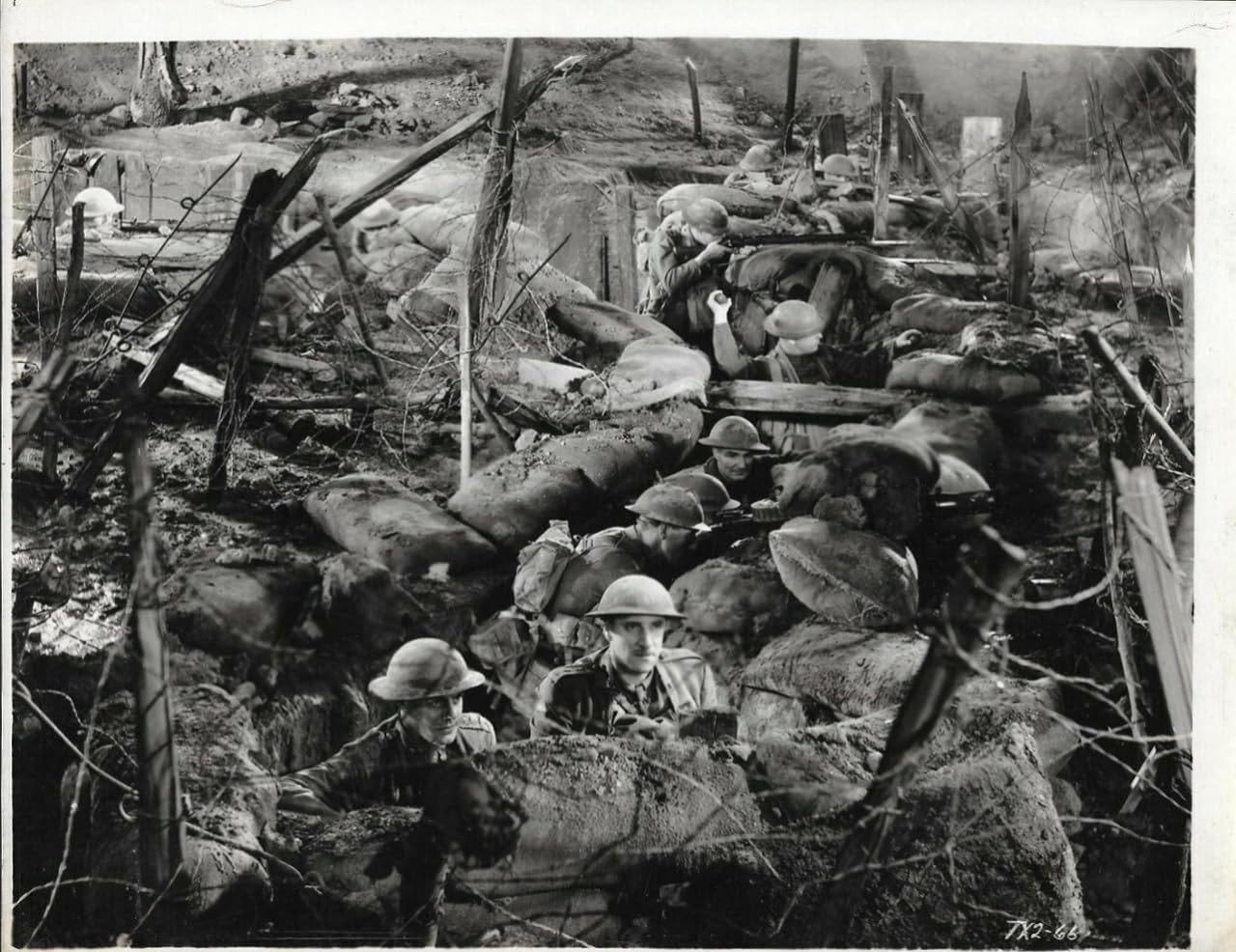

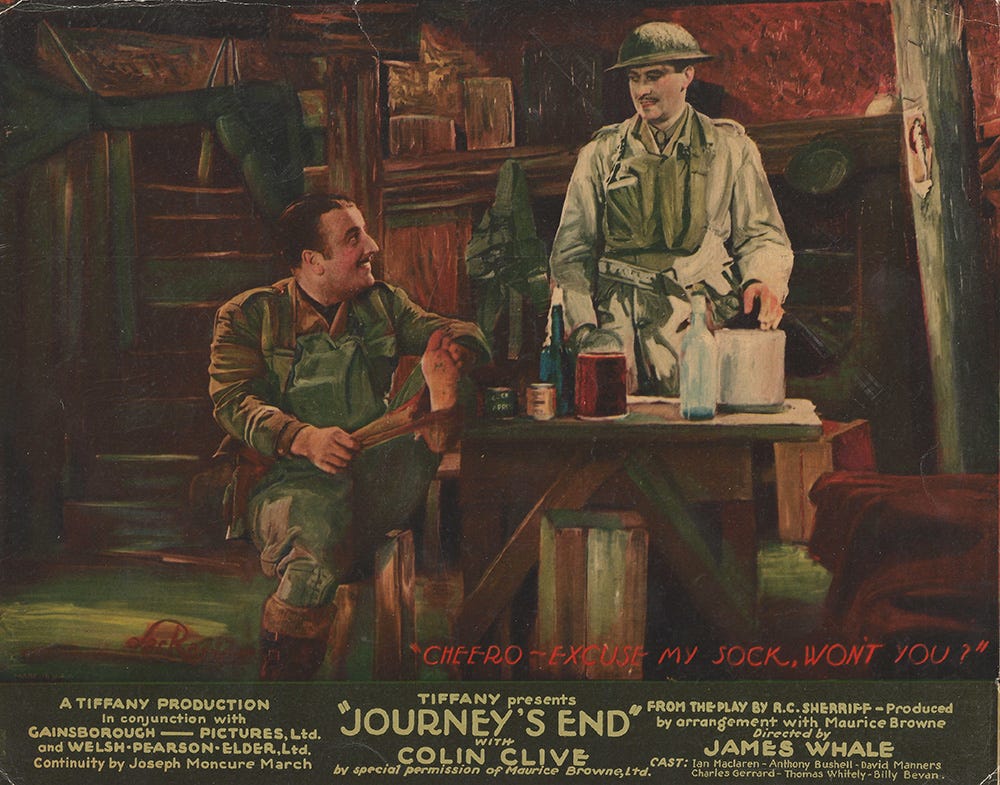

I have used images from the film version of “Journey’s End”. I believe these are the correct plays discussed in the essay, they are relatively unknown today. I will make a correction if I can find out more information, there are no references in the published version I have access to.

More than ten years have passed since the World War, and no one in Germany dared to consider this great historical event as material for the theatre. The spectator, and above all one who knows the war from his own experience, cannot help thinking that this period is still too recent, that the subject is still too sensitive to be grasped with certainty, let alone mastered.

The reason for the lack of achievements lies in the fact that war is a process that belongs to the realm of the heroic. However, in this sphere the forces capable of dealing with it are completely lacking. Instead, the attempt is made solely from the world of morality, and the viewer learns upon returning home that the author considers war to be good or bad, moral or immoral, just or unjust. Moreover, there is no German war play where doubt can remain regarding which political party the author belongs to. But since war is subject to laws of an entirely different order, we cannot be content with a process which confines itself to pinning political or ideological flags on it, passing over its full form, force, and passion. No one doubts that the mixture of brothel, persecution, and repression depicted in Toller’s play “Feuer aus den Kesseln” was possible. It all depends on what you see, and one can also imagine an attitude that take part in the way Achilles relieved himself. It is just that in the context of war, such things are no more important than the plumbing in a house. But we should not argue over matters of taste.

War is the best example of the richness of life in terms of victories and defeats, sacrifices and symbols, triumphs and passions. To fly over this landscape requires wings more powerful than those given to the ephemeral. Therefore, it will probably be a long time before a force capable of realising the true meaning of a world war is manifested. For it is enough to reflect that it was a confrontation of mythical proportions, a struggle between the most intimate figures of life, the meaning of which true warriors grasped in their blood and knew how to express in battle. That is why only in them will the future capture the symbol of this era.

*

If some plays from abroad make a more favourable impression, it is because they are on a higher level than polemic, namely objectivity. This may be explained by the fact that the war has left less painful scars in these countries than at home, so we can more quickly close the files on many questions of guilt and consider it a simple fact. Even if the actual treatment cannot achieve a heroic life, which relates to more than facts, it can still provide snippets of the figures of the war, since they can never be seen in their sharpness through moral spectacles. Thus they succeed in doing what the German plays fail to do, namely, not to bore the spectator; for a slice of life grasped with acuteness and clarity always has its charm, while mere sentimentality is paper-thin.

Thus the American play “Rivals” represents the elemental side, the natural, primitive essence of man’s life. Though the characters portrayed in it are not developed in a dimension that could claim the title of tragedy, on the other hand, it is quite heartening that none of them indulges in social, humanitarian, or chauvinistic phrases. This play has more the character of a crude farce set against a bloody background. Its characters are neither particularly brave nor particularly fearsome, neither particularly good nor particularly bad – they have one virtue, and that is vigour. This is why the war prevents them from having the conversations you might have at Communist tea parties or the Young Men’s Christian Association, but this is a landscape where you live and let live, or die and let die. For them, nothing is more remote than wasting their time, which they know is in short supply, on ideological debate. When they are not at the campfire, they are occupied by broad creature comforts, they like to eat well and plentifully, they like to drink even more, and, if possible, not sleep alone. This is not heroic, but it is genuine, grown on the elementary soil of war and readily comprehensible to us; therefore these fellows do not bore us, and one enjoys watching them, just as one cannot watch Falstaff, after whom these characters are modelled, without pleasure, because he is not related to the models, but to the archetypes of life.

*

In the English play “Journey’s End”, male society is viewed from a different angle. Whereas in “Rivals” the common ground is the natural force of life, represented by professional warfare, here it rests on a more refined condition, the basis of which is civilised society. The exemplar of such a society is a small group of company officers who maintain a kind of rough comfort in their dugout and carefully endeavour to insulate them from the war which lies in wait, a few steps from the entrance, and drifts up to them as a primitive and destructive force. Only reluctantly does one leave this small dwelling - filled with candles, cigarette smoke, and steaming toast - to stand guard outside or hide in no man’s land. But one leaves, even if it is very much doubtful that one will return, because it is in accordance with the laws of decency, which are themselves an expression of a deeper legitimacy.

This is the real conflict in the play, which is varied in many ways. Only the youngest officer seems unaffected by it, but this is because he has only been out for a few hours and does not yet realise the danger. The phlegmatic Trotter does his job like a well-oiled machine, though he makes no secret of the fact that he does not like “old ruins in no man’s land” at all. The elderly gentleman Osborne bids farewell in front of one of those corridors from which one never returns, saying that he does not like “to leave a good pipe when there is still a pleasant glow in it.” Captain Stanhope can only keep his balance through copious consumption of alcohol. The hysterical Hibbert becomes nauseous at the slightest extraneous noise. There is no doubt, however, that he must be grinding his teeth. Again, it is good to see this expressed in terms of composure rather than entertainment.

The technical treatment of war in this play is particularly appealing. It is the monotony of the last war that presents the greatest difficulty for any creation. Hence the attempts to break this monotony by interweaving one plot with another, such as the erotic. In “Journey’s End” this has been abandoned, instead there is a trick, turning the dugout itself into a neutral territory, a second space for the audience from which the war is watched like an animal through bars. In this way, the threatening and dangerous nature of war becomes particularly vivid as it clashes with seeming security.

It would be good if Germany also drew inspiration from these plays. It is not always necessary to talk about war, and it is especially unpleasant when this is done by people who lack even a modest relationship to it. A playwright cannot choose a subject like a man chooses an item in a shop; his language is determined by love and responsibility. Even the naïve mind has little interest in what war represents in the imagination of a wine merchant, a popular orator, or a party functionary, one can only feel interest where, however modestly, the questions that comprise the war itself are touched upon.