From Die Kommenden Titanen

Published in 2002

Part One is available here:

The Coming Titans - Ernst Jünger (substack.com)

Second Discussion

It is now late autumn. We have returned to Wilflingen with the intention of staying as long as necessary for the interview. We have made the final arrangements on the phone, and when we arrive Jünger is already waiting in the living room. While Liselotte does the honours and seats us at the table in the usual order for guests, we exchange our first words. The vintage wine we have brought with us arouses great interest in Jünger, who caresses it like a connoisseur and sees to it that it is well placed in his reserve. The weather outside is dreary and grey, but the conversation, which gradually livens up, warms the atmosphere. Over the past few months we have been preparing for the new meeting and have drawn up a series of questions which have been supplemented and reworked right up to the last minute. We discussed the final details the previous evening in a country inn between Tübingen and Wilflingen, where we stayed overnight. When it comes down to it, our catalogue proves to be a superfluous zeal: a few hints are enough and Jünger unleashes his memories, which overlap and overflow in a conversation we hardly order.

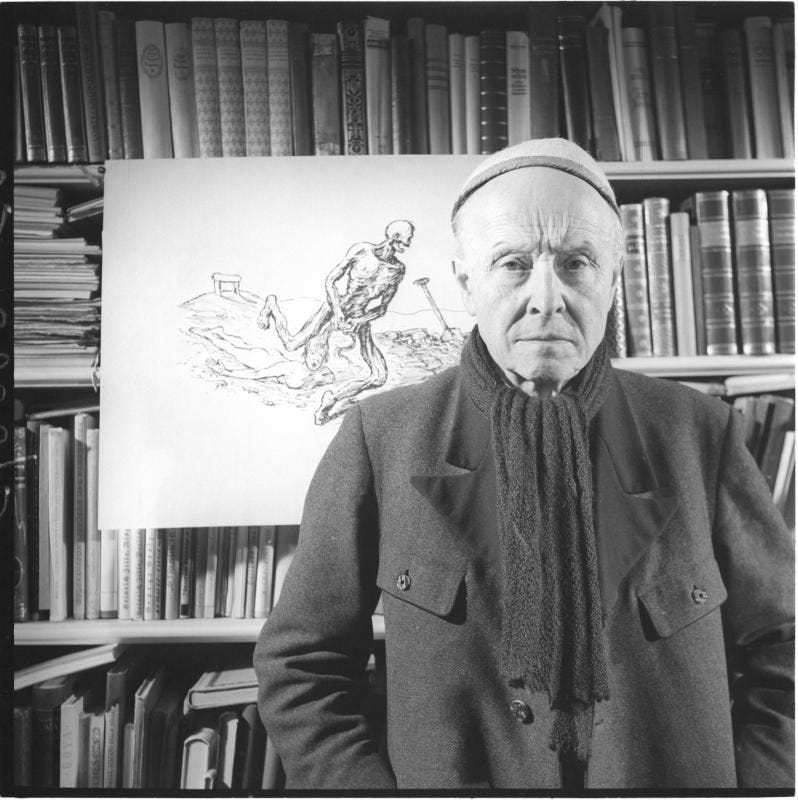

You had multiple and very heterogeneous acquaintances. Thanks to the early success of Storm of Steel , the most diverse doors were opened to you, even those that were inaccessible to others. One of your first important encounters, for example, was with Alfred Kubin. How did you meet him?

During the First World War, in 1914, I happened to see a pen drawing of him entitled Der Krieg, which I found striking. A couple of years later, on my way back from leave and on my way to the front, I stopped in Cambrai to spend the night. It was evening, and not knowing what to do, I slipped into the military bookshop which was still open. It was there, rummaging through the books - which were actually quite few - that I came across Kubin’s fantastic novel The Other Side. I began to leaf through it and saw that it contained numerous illustrations by the author. I bought it, and I remember spending the whole night awake, eagerly reading the story of Perla, the capital city of an imaginary kingdom whose ruin Kubin tells us of. In Perla you cannot see the sun, the moon or the stars, everything is covered by an oppressive greyness. It is ruled by Patera, who, although he lives withdrawn and inaccessible in his palace, is present with his spirit in every corner of the kingdom. Until Hercules Bell, a rich black man, arrives in the city and starts a fight to oust Patera. Their conflict, which symbolises the antithesis between the death drive and the will to live - the two fundamental forces of existence - causes the ruin of Perla, which Kubin describes in dark, apocalyptic tones, inspired by Bruegel’s famous painting The Tower of Babel. It was for me a fantastic key to understanding the decline of a world lost forever, the happy world of old Austria and the Wilhelmine bourgeoisie. I was so fascinated and impressed by it that I wrote a short poem dedicated to Kubin and sent it to him. He found it very charming, and so we began a correspondence that grew and continued for decades. Naturally, the desire arose to meet him personally, and at some point I went to see him. If I remember correctly, it was in the autumn of 1937.

What was your impression when you met him in person?

He came to pick me up at the railway station closest to the small castle where he lived. During the journey I had felt tense, imagining the magical moment when I would meet him. He was more corpulent than I had imagined. He in turn was surprised to see my petite build, since he had imagined me as one of those tall knights at King Arthur’s Court. Kubin was an extraordinarily sensitive man, he loved the comforts of life, and believed that matriarchy was the best form of organisation of social coexistence. In his house, in the absence of his wife, we were served all the time by two maids who took care of us. I had the impression that Kubin lived isolated in his home like a silkworm cocooning itself in its silk. In the evening we stayed together again and, between one glass of champagne and another, Kubin told me about his dreams and fantasies. Meeting him in person gave me a better understanding of the atmosphere of the novel The Other Side, much more than I had been able to describe in the review I had done years before for Niekisch’s magazine Der Widerstand. I believe that Kubin was, after E.T.A Hoffmann, the greatest author of German-language fantasy literature. In a short essay, The Dust Demons, I wrote about the influence his work had on me.

And what was Kubin’s attitude towards you?

An understanding was formed immediately. He gave me a copy of his novel in which he had written a short poem as a dedication:

Wenn Deine Seele, Dein Herz erschrickt vor Abgründen, die kein Auge erblickt, springe hinab, gesegnet Dein Fall, Wahrheit umgibt Dich dann überall.

I mentioned this in the edition of the correspondence I kept with him. We remained in contact and met on other occasions. I remember that during the Nazi period, when I visited him, Kubin showed me a photograph of a mass demonstration with thousands of people cheering a speaker. The individual participants were so tiny that they looked faceless. He told me: ‘You could paste many more copies of the same picture here, one next to the other, ad infinitum...’. In the 1940s Kubin illustrated an edition of my account of the trip to Norway with Hugo Fischer: Myrdun. Briefe aus Norwegen.

During the short but intense season of the Weimar Republic you sided with the opponents of the Republic, but your acquaintances seem to be oblivious of the distinction between left and right. You had a very close relationship with Ernst Niekisch, an important figure at that time, leader of the National Bolshevik movement, whose political programme is perhaps the most significant expression of the attempt to find a third way, beyond the traditional right and left...

Yes, I was in close contact with Niekisch. My brother and I wrote for his magazine Der Widerstand, which was founded during the Weimar Republic and remained alive for some time even after the National Socialists came to power. Der Widerstand was just the right name: Niekisch, whose intransigence was in direct proportion to the difficulty of defining his political programme, truly embodied an ethos of resistance. Moreover, the title seemed to be well suited to the situation and the difficulties of the moment. Against whom or what should we resist? Against the Weimar Republic, against the Versailles diktat, against the bourgeoisie, against the Western world and its economic and capitalist imperatives. And the Western world for him was represented by England with its mercantile and colonialist spirit, by Paris with the war reparations imposed on Germany, by Catholicism, and by German social democracy. In contrast, Niekisch admired the Russian soul and the Prussian order, with its sense of state and its people’s army. In his political programme he wanted to merge the principles of Prussianism and Bolshevism. His models were Ranke as a historian and Hegel as a philosopher. He preferred Kant to Nietzsche and Schopenhauer, but found Spengler especially interesting. This is enough to understand how difficult it is to trace his thought and his political project back to a common denominator.

In Berlin in the early 1930s, I once visited him at his home with Carl Schmitt and Arnolt Bronnen, and he proudly showed us the drafts of his forthcoming book Hitler, ein deutsches Verhängnis [Hitler, a German Calamity]. To publish such a book was a reckless, if not suicidal act. I pointed out to him that when faced with a charging, angry rhinoceros, it is perhaps preferable to dodge it rather than resist it. His friends, including myself, advised him to emigrate. He replied that in charging a rhinoceros, moral principles are not at stake. In the political struggle, however, man is at stake, and so one must resist, in the name of morality.

Your collaboration with Niekisch dates back to the time when you developed the ideas that were later set out in The Worker...

When I published this book of mine, Niekisch was among those who were most favourably impressed. Indeed, he was enthusiastic. Various comments, discussions and positions appeared in his journal. After he was arrested, convicted and imprisoned in 1937, I kept in touch with him through his family. For a long time, I hoped that once he was released from prison, he would be able to resume his political commitment and promote the nationalist cause. Unfortunately, the years he spent in prison had undermined his health. He fell seriously ill and never regained the necessary energy. He never really recovered.

However, Niekisch was one of the few who immediately understood the meaning I wanted to give to the figure of the Worker. I have to give him credit for this, because even very sharp minds like Spengler and Carl Schmitt did not understand me, indeed they misunderstood my intentions. Spengler and Schmitt did not accept my theses because they thought I wanted to sing the praises of the proletarian. I saw the Worker as a kind of Promethean figure, not as a proletarian. Niekisch understood this immediately. He understood that, far from wishing to propagandise for a new party, I had simply described the new reality not in the empirical terms in which sociology describes a new order, but by focusing on the figure and the essential features of the Worker. For me it is therefore a form that has an almost metaphysical character, as metaphysical as the idea of Goethe’s Urpflanze. In an article on the Worker, Niekisch made this association.

You were also politically engaged in Berlin at that time. Your youthful writings and publications are often cited as one of the sources of inspiration for the conservative revolution.

They are probably more the expression than the inspiration. In any case, they testify to my conviction, then and always, that to be conservative in the highest sense, that is, in the true sense of the term, it is not enough simply to live off one’s inheritance, to preserve what one already has. I am often reminded of these writings by critics today. And even rebuked. It is strange that people cling to those short, occasional texts, written more than half a century ago, rather than to everything I wrote later. However, I also recognise myself in them, because after all they bear witness to a certain phase of my life. But I am convinced that they have the same character as newspapers: they are only interesting if you read them on the day they come out. Or they become interesting a hundred years later.