This is Carl Schmitt’s 1929 review of Wesen und Werden des faschistischen Staates. Erwin von Beckerath: Berlin (Springer) 1927.1

This book presents with exemplary clarity and consistency the historical development, sociology, and ideology of Fascism up to 1927. The author continued this theme in “Idee und Wirklichkeit im Faschismus” (Schmollers Jahrbuch, vol. 52). Despite many earlier good and thorough German works on fascism, only this book achieves the level of objectivity and scientific clarity that allows for certain, fruitful discussion. The book also has a number of other qualities that enhance its value. It takes an objective and clear stance, without biased party-political limitations, and even dares to make prognoses. This distinguishes it very favourably from the statements of enthusiastic commentators and blind isolationists, which unfortunately include prominent German academics; and it does not abuse notions of objectivity and scientificity to avoid the clear knowledge and formulations of a wait-and-see attitude. It goes without saying that the book’s predictions do not belong to the type of prophecies one could read in 1923-1925, and not only in newspaper articles, the best example of which is the ostensibly apolitical statement from the scientific conference which proclaimed in February 1925: “Mussolini’s fall is only a question of time.”

Given the clear and coherent presentation of such a book, it is not possible to repeat in a short review its very concise and succinct content, one can only highlight some points which arise from the perspective and discipline of the commentator. I would therefore like to start with a few remarks on state theory. On constitutional questions I can refer to Gerhard Leibholz’s excellent treatise Zu dem Problem des faschistischen Verfassungsrechts (Berlin 1928). Concerning the theoretical construction of the state itself, I believe that the author does not sufficiently illuminate the specific problems of the state, which can be summarized in the following question: Is it conceivable that today a state should play the role of a superior third party in the face of economic and social antagonisms and interests (this is the claim of the fascist state); or is it necessarily only the armed servant of one of the same economic and social classes (the well-known Marxist thesis); or is it a kind of neutral third party, a pouvoir neutre et intermédiaire (which it is in fact, to a certain extent, in Germany today, with the remnants of the old bureaucratic state playing the role of such a pouvoir neutre)? It is precisely the dominance of fascism over economic interests, be they of employers or workers, and the attempt, which can be called heroic, to preserve and strengthen the dignity of the state and national unity in the face of a plurality of economic interests, that is impressively brought out in von Beckerath’s presentation. But his interest in state theory focuses mainly on ideology and on the tension between fascist ideology on the one hand and democratic and parliamentary ideology on the other. As a result the real difference in state theory is too often confused with the contradiction of mere ideological keywords. This probably explains why fascism is placed in absolute opposition to democracy (which should distinguish it from Bolshevism; pp. 147, 149), why it is perceived as something absolutely anti-democratic, when in fact it is only in absolute opposition to the liberal decay of genuine democracy. It seems to me that the author has not stressed enough the difference between democracy and liberalism, which of course has long been known. The distinction is fundamental, it is based on the opposition between political thinking and economic thinking in general. I refer to the highly witty and elegant, but ultimately incorrect, formulation that fascism, at least in its “first hour”, was “a kind of l’art pour l’art in the political sphere” (p. 25); and the misleading label “romantic” (p. 24) results in a lack of clarity about the nature of bourgeois liberalism and a conflation which suggests that 19th century confusions have not yet fully been renounced.

Consistent liberalism is rooted partly in economics and partly in ethics and is also an elaborate system of methods of weakening the state. It separates everything specifically political and specifically statist from the ethical and economic. Democracy, on the other hand, is a concept that is just as specifically political. True nationalism, compulsory military service, and democracy are “threefold and inseparable”, and the Caesarist democrat is an old historical type (Sallust!). The great growth of the civic and national consciousness of the masses of Italians, especially among the peasants, the “colonists” - a growth which Fascism in any case ensured and which a good and unbiased observer like Paul Schaeffer calls the great achievement of Fascism - cannot be contrasted with democracy. The fact that fascism refrains from elections, that it hates and despises all “elezionismo”, is not anti-democratic, but anti-liberal, and stems from the fair recognition that the present methods of individual secret voting endangers the whole state and the political with total privatisation. This completely excludes the people as a subject in the public sphere (the sovereign disappears into the voting booth) and reduces the formation of the state will to the sum of secret and private individual wills, i.e. in reality – to uncontrollable mass desires and grievances. Protection against their truly disintegrating effect can only be achieved by creating, in the spirit of Rudolf Smenda’s theory of integration, a legal obligation for the individual citizen to have not his private interest in secret voting in mind, but the good of the whole – a weak and highly problematic defence in view of the realities of social and political life. Equating democracy with the individual secret ballot is 19th century liberalism, it is not democracy. Even the new Fascist law on political representation of 17 May 1928, which allows voters to say “yes” or “no” to a list of candidates presented by the government, is undemocratic only in the sense of this liberal privatisation. It actually leads to a plebiscite, as Beckerath also acknowledges (Schmollers Jahrbuch, vol. 52, p. 213; also Leibholz, p. 27). But there is nothing undemocratic about the plebiscite. Even the most radical and direct democracy cannot overcome the fact that the people can only welcome or say “yes” or “no”; and given the inescapable dependence on questions and lists of proposals, it is precisely political and consequently also democratic to let questions and lists of proposals come from the government and not to entrust them to anonymous cliques and groups of interested parties who fabricate them in deepest secrecy and submit them out of an opaque and irresponsible darkness to a partly party-organised, partly helplessly wavering mass of individuals voting in secret. As things stand today, in no country is the struggle for the state and the political a struggle against genuine democracy, but it is equally necessary that it is a struggle against the methods by which the liberal bourgeoisie of the 19th century weakened and overthrew the monarchical state of that time, now long since finished.

It is particularly striking that states such as Bolshevik Russia and Fascist Italy are the only ones that have attempted to break with the traditional constitutional cliché of the nineteenth century and have expressed major changes in the economic and social structure of the country, as well as in the organisation of the state and in the written constitution. Curiously, the large and leading industrialised countries (of which Italy is not yet among them) retained the constitutional system inherited from 1789 and 1848, despite all the changes in their socio-economic structure. The Weimar constitution of 1919 also essentially corresponds to the old type and, as Rathenau rightly said, could easily be from 1848. The Bolshevik and Fascist constitutions, on the other hand, are extremely modern in this respect, that is, in recognising new economic and social problems in the organisation of the state, and they are true “economic constitutions”. Let me explain myself beforehand in the following way: it is the non-intensively industrialised countries, such as Russia and Italy, that can today provide themselves with an “economic constitution”. In highly industrialised countries, however, the domestic political situation is entirely determined by the phenomenon of the “social equilibrium structure” between capital and labour, employers and workers. This phenomenon, first recognised and named by Otto Bauer, was later examined by O. Kirchheimer in an interesting article in Zeitschrift für Politik (vol. 17, 1928, p. 596) on state and constitutional theory. If the fact that employers and employees compete with roughly equal social power, and that neither group can in any case impose a radical solution on the other without a terrible civil war, is today an integral part of the highly developed modern industrialised state, then fundamental social solutions and constitutional change are impossible by legal means, and everything that exists at the state and government level is more or less only a neutral third party (rather than the highest third). The domination of the state over the economy can only be achieved through a closed and orderly organisation. Both Fascism and Communist Bolshevism need such an “apparatus” to establish their domination over the economy. The sociological terms that von Beckerath uses here (p. 141) are terminologically unclear as they do not sufficiently distinguish between party, order, and caste. However, for thinking about the theory of the state, it is important to make a distinction even in the language used. How can the state be the highest and most powerful third party if it does not have a strong, firmly established hierarchical organisation, closed in on itself and therefore not based, like the party, on free publicity? Only a new organisation of this kind is mature enough for this enormous new task. The fate of Germany is such that already a century ago it produced a magnificent philosophical theory of the state as an upper third, extending from Hegel through Lorenz von Stein to the great economists (such as Schmoller and Knapp), which then fell prey to a rather crude levelling and could easily be denounced as the doctrine of the authoritarian state, because in sociological reality no new organisation created with sociological awareness the situation which corresponded to it, but only a well-disciplined and mechanised bureaucracy in connection with a traditionally hardened, nationally confusing plurality of dynasties whose ideal basis was the politically paralysing concept of legitimacy.2 Fascism, on the other hand, attaches importance to being revolutionary for good reasons.

Von Beckerath also points out that the Fascist stato corporativo, with its attempt to unite and harmonise employers and workers, has not yet succeeded. “The tensions are resolved by the victory of the government.” The fascist state decides not as a neutral third party but as a higher third party. This is its superiority. Where does this energy and this new power come from? From national enthusiasm, from Mussolini’s individual energy, from the movement of the participants in the war, and perhaps from other causes – all this is described with exemplary clarity in Beckerath’s book. But the general prediction he then makes seems to me, in the question’s phrasing, to miss the point. The prediction is that the ideology of the majority will decline as economic and political power is concentrated in the hands of the few, and that the authoritarian state will regain its position in the Western cultural community by transforming political ideology (p. 154/155). I do not want to pose the question in such a way that a prognosis must be ideological, but rather to ask who will the apparatus created by Mussolini ultimately serve, if it continues to function without the present engine, according to human calculations, the capitalist interests of employers or the socialist interests of workers? I believe that to the extent that it is a real state, it will in the long run serve the interests of the workers, because they are now the people, and the state is the political formation of the people. Only a weak state is a capitalist servant of private property. Any strong state - if it is really a superior third party and not just identical with the economically strong - shows its true strength not against the weak, but against the socially and economically strong. Caesar’s enemies were the optimates, not the people; the state of the absolute prince had to assert itself against the states, not against the peasants, etc. This is why employers, and especially industrialists, can never fully trust a fascist state, but must assume that one day it will be transformed into a workers’ state with a planned economy. This assumption is in line with some of Beckerath’s explanations (e.g. p. 143) and has recently been openly expressed by Paul Schaeffer in a very interesting and important article (Berliner Tageblatt No. 613 of 29 December 1928). From this we can conclude - a fine example of the cunning of the world-historical idea - that just as Bismarck realised the basic elements of a genuinely liberal programme under the ire of liberals in 1863-1870, so Mussolini would create a socialist armature in a fierce struggle against the official guardians of socialism. This does not preclude some liberal backlash when Mussolini’s leadership ended. But, in my view, such a rollback would be nothing more than an attempt to avoid the immanent consequence and direction of the current fascist apparatus leading to a state-planned economy, and this attempt would only be possible at the cost of the complete dismantling of the entire apparatus and the blind restoration of the old liberalism, a restoration which Beckerath declares impossible at the end of his article in Schmoller’s Jahrbuch.

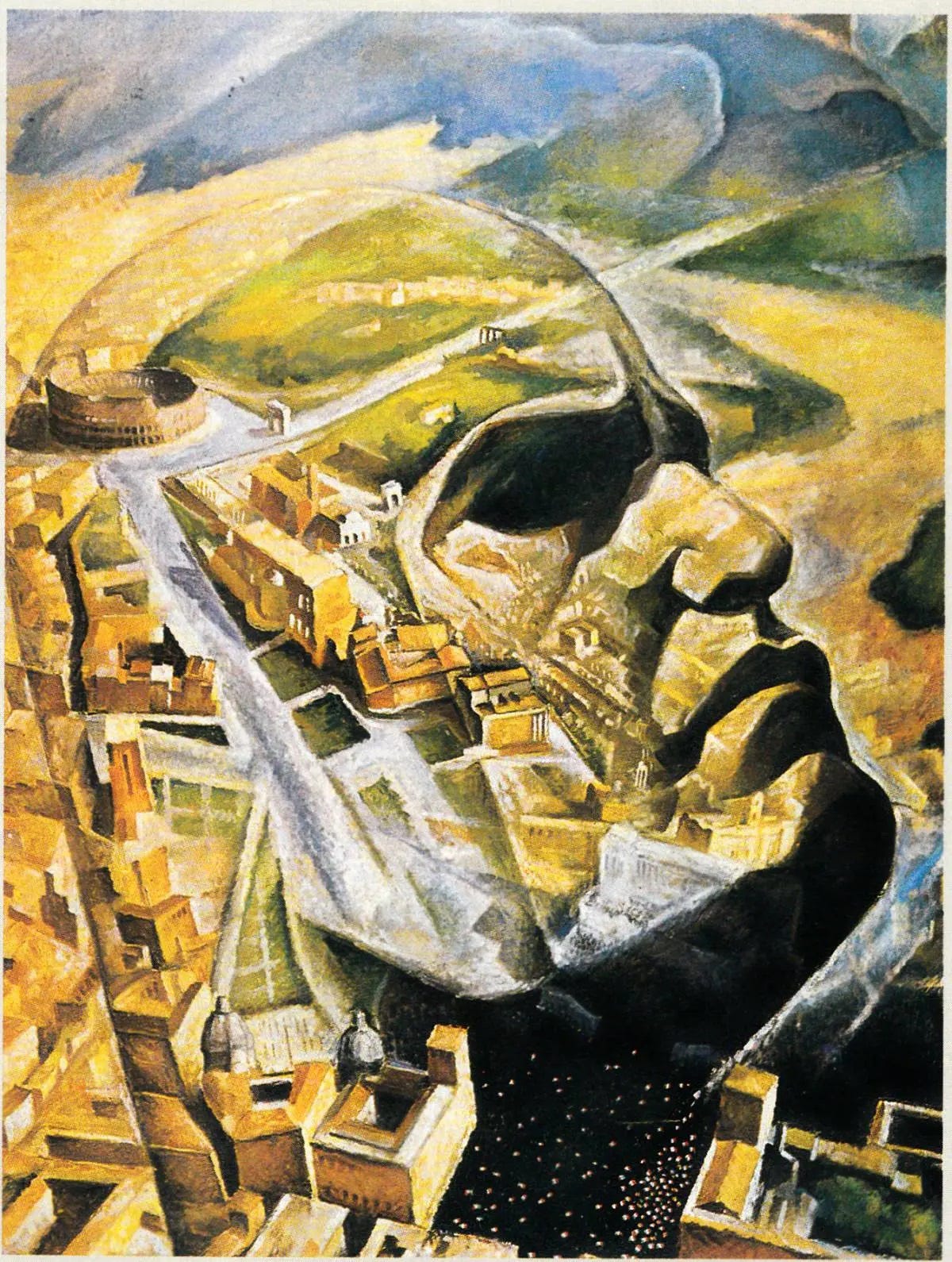

Finally, a few words to conclude with an explanation of the stato etieo and state ethics of Fascism. Fascist conceptions of the state should not be commensurate, even on the contrary, with the norms and words that have become natural in the European bourgeoisie since the eighteenth century. All these words are indeed part of the atmosphere of ideological deception that millions of people feel and hate today. Like all strong movements, fascism tries to free itself from ideological abstractions and illusory forms in order to reach a concrete existence. The fascist ethos is also based on a sense of deception, which has existed everywhere since the nineteenth century, which is not only a proletarian feeling and which found stronger expression in the Latin countries than in Germany after the world war. The fascist state wants to become again a state with old honesty, with visible rulers and representatives, not a facade and an anteroom with invisible and unaccountable rulers and supporters. A strong sense of connection to antiquity is not simply an embellishment, which von Beckerath certainly does not suggest. It can be understood in terms of this reaction against abstract depoliticisation, in relation to the simple historical fact that the great state of the European continent has always been, in the true sense of the word, a classical entity, and must remain in the tradition of classical thought. This applies to the states born of the Renaissance and the Baroque, to the great periods of the French state and the Prussian state; it also applies to Hegel’s last great philosophy of the state, whose roots run deep into antiquity. If fascism feels its superiority over Marxist socialism, this sense of superiority affects above all the socialist view of man and its abstract, ghostly ideological monism, the genuine liberal heritage which proletarian socialism will carry with it only so long as it does not possess state power, and which fascism considers to be overcome because it recognises with old simplicity the concrete plurality of peoples and nations, the plurality of bourgeoisie, and plurality of proletariat, and knows that the Italian people can preserve its concrete way of national being only with an array of political will.

As a German, one can only hope that the German people will be spared another fate, which the young Hegel hinted at: “It is a higher law that the nation from which a new universal impulse is given to the world will itself perish in the end before all the others, and its principle, but not itself, will endure” (Schriften zur Politik, Ausgabe Lasson, p. 96).

Nice.I like,it..