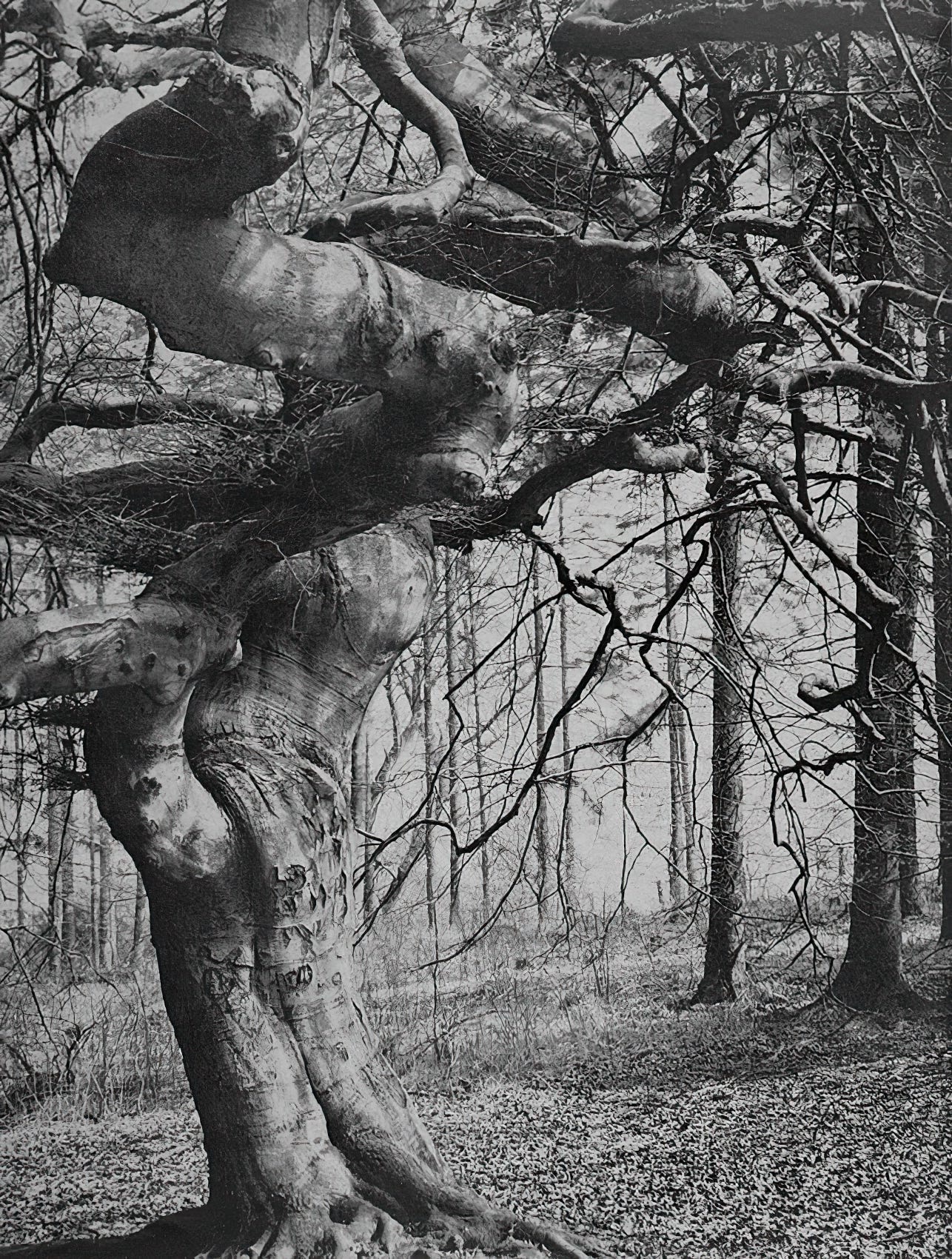

First printed privately in 1962 in Trees by Albert Renger- Patzsch, a photographer from the New Objectivity movement. His work is included in part here.

In every language there is a treasure of words that constitute its being. The poem lives from them. As if a bell were struck, they awaken an aura of echoes in us. The word "tree" is one of them.

The tree is one of the great symbols of life, perhaps its greatest. At all times it has therefore been admired, honoured, and also revered by peoples and nations. Its height and depth, its age centuries old, its majestic, protective growth have all seemed worthy of veneration.

The Persian kings had old plane trees decorated with golden chains and appointed guards to serve them. Among the Germanic tribes, the Allfather was worshipped in ancient oaks, and the cosmos was seen as an ash tree. From the crowns of the winter oak, the druids cut the mistletoe leaves with a golden sickle to crown the horns of white bulls; the yew tree, as a tree of the dead, shielded the graves of Celtic cemeteries. In the rustling of Dodona’s sacred grove, the priestesses heard the voice and the counsel of the supreme Zeus. They praised him in the round:

Zeus was, Zeus is, Zeus will be, O Thou mighty Zeus!

Even today, in the deified world, we are gripped by trepidation when we hear the rising and falling of the wind in the forest, which now barely rustles the leaves and then plays with the high trunks as if on the strings of the weather harp. There, even more deeply touched than by the sound of the organ, something old and long forgotten awakens in us.

Floating back and forth over treetops how it catches its breath, surges and roars and moves on – and becomes still – and whooshes.

This from Peter Hille, an itinerant and long-forgotten poet who often took refuge in the forest, the “mossy dreamer”. In his life, like many before and after him, he had sought comfort and freedom in the forest. Our brother man has often abandoned us, brother tree never has.

What was it that comforted us in this rustling? In vain we seek to remember the encouragement when “above all peaks” is peace and the song falls silent. So we try in vain to interpret the dream in the bright light; we do not find the solution. We must descend again into the night – there it waits for us. The poet suspects it:

Just wait: soon you too will rest.

Does the tree belong to the father or to the mother world? That cannot be answered in one sentence. As the height is attributed to the father, so we would like to attribute the depth to the mother. We find protection under the crown, but security in the network of roots. The branches spread out like arms reaching for the sky, while the roots take hold in the soil.

What breathes in the light is visible to the eye, but what feeds on the juices of the earth is hidden. It is the power of one and the same being that gains height here and depth there. What we behold on high and what the depths conceal from us has outgrown a point and divides the day and the night like image and reflection.

Image and reflection want to show a miracle in the unfolding; they refer to a being that determines the dimensions. When we walk through the forest, when we look at an old tree, a third is always present, which unites image and eye and which unites height and depth.

From time immemorial, man has taken the tree as a model when reflecting on his coming and going. When he remembers those who were before him, he descends in spirit to the roots. There are the ancestors whose image is soon lost in myth and then in humus. Where the fathers and ancestors are honoured, the tree is also cherished.

When man sees the light, a new eye opens on the tree of life. Before him have been many who rest in the earth, and after him many will strive towards the light. Soon he too will join the ancestors, will be ancestor and progenitor, for the life of the individual is short, as the Psalms already lament; it is like the grass that is cut in the evening, or like a grain of sand that falls through the hourglass. But in it, genealogy and family tree intersect as the roots and branches of the great succession that is lost in the darkness of time.

The tree of life, like the hourglass, is a symbol of the times that intersect in the timeless – there is the waist, the root crown. There is the point we call the moment; we see the past spreading out below, the future above.

In the tree we admire the power of the archetype. We sense that not only life, but the universe spreads out in time and space according to this pattern. It repeats itself wherever we turn our eyes, down to the drawing of the smallest leaf, down to the lines of the hand. It is followed by the rivers from the watershed on their way to the sea, the stream of blood in the light and dark veins, the crystals in the crevices, the corals in the reef.

In the archetype, the incomprehensible is sensed, which spreads out in the appearance. The moment conceals and hides the supra-temporal, much like the material axis of the wheel conceals the mathematical one. The fullness of time is nourished from the timeless, the turnaround is nourished from the resting. In this way, even the unfolding of the smallest seed is arranged in the last around the inextensible – not around a spermatic, but around a pneumatic point. Only then are there above and below, right and left, roots and branches, life and death. This is a miracle that can only be understood in a parable like that of the mustard seed.

The tree as the archetype therefore appears not only in the tree of life, but also in the tree of the world. We see it in all elements, in the stone, in the river, in the fire, and also in the stars.

It is therefore not surprising that in the world of plants the tree is not represented as a crowning achievement which has been attained through a long and difficult ascent. Man is regarded, perhaps all too humanly, as the goal and crown of the living world.

No, there are many genera that aspire to the tree and represent it in their own way. The oak, the pine, the dragon tree, the eucalyptus are trees “by themselves”; they are so in essence and not in kind, are related in spirit rather than in blood. Basically, every plant has the potential of the tree. The principle is already embodied in the fungus that sprouts from the mycelium overnight. Families whose species we only know as herbs, such as ferns and horsetails, produce trees and forests in other latitudes or at other times. We can easily think of grasses like the papyrus as trees. Some woody plants, such as the lilac and the salt willow, grow both as shrubs and trees. In a garden near Jericho this spring I was surprised by the sight of a strong tree, its profusion of flowers foaming down in purple cascades. It was the bougainvillea, which I had previously only known as a climbing plant. Furthermore, trees in the deserts, the mountains or in the far north wither to bush and dwarf forms, like our birch in the Lapland high moors. Finally, the gardener can transform shrubs into trees by cutting out the side shoots, or, conversely, trees into shrubs by cutting off the tops.

If we have a fixed concept of the tree in all this, it is because our conception orients nature. This conception of the tree is closely connected with what the ancients called physiognomy. We see the tree as something grand in which nature gains individuality or, better, personality; its growth testifies to life in a higher than purely vegetative or zoological sense. This immediately creates a sense of dignity and reverence.

Until the end of the 17th century, botanists still kept trees and shrubs quite separate from herbs and perennials. It was not until Linnaeus’ sharp eye, like so many specialists, that this too was recognised as incidental. Neither in his natural nor in his artificial system does he recognise tree growth as a defining attribute of its genus.

The physiognomic decision is not affected by this. We instinctively know what to address as a tree and what not. The tiny pine that the Japanese grows from ancestor to grandchild in a bowl is a tree – the huge stem in the bamboo thicket, on the other hand, is not. The Italian poplar is a tree, even though it already divides into a plurality of branches at ground level, like fire in flames. Even where the tree doubles or multiplies above the root crown it maintains personhood, unlike the shrub. We then address its trunks as twins or brothers. Such formations are familiar in every landscape. Just as some streams in their waterfalls are known as “the Seven Sisters”, so trees in the woods or in the fields are famous as “the Seven Brothers”.

The question of the ideal form of the tree produces just as many different answers as the forest produces trees. Psychology has made one of its games out of it. Of course, it would be better to speak of characterology here too, as with every physiognomic decision, because it is basically the question of its inner growth and nature that the person asked about his tree answers. He chooses his totem image.

Here, too, it can happen that one cannot see the forest for the trees. There is no ideal form of tree; every species carries its ideality within itself. If this were not the case, there would be no style in art. Man’s inclination, his preference for certain plants and animals speaks of a statement that reaches deeper than his art, unless one wants to see in art itself a statement through which man represents his being-as-it-is. The essence of art remains anonymous. Whether he chooses height, depth, youth, age, grace, dignity, defiance, sadness, whether he is addressed by the crown, the umbrella, the bouquet, the lance, the dome, the pyramid, whether he chooses the busy poplar, the alder by the marsh, the pine in the dry sand, the weeping ash or the oak streaked by lightning - they remain allegorical statements that reach down to the unique. There, the chorus of voices unites to form the great echo of “This is you.”

There are monoecious and dioecious trees: those that bear both male and female flowers, such as the alder and the chestnut, and others in which the sexes are distributed among the stems, so that one can speak of male and female individuals.

In the date palm, even individual affection is found. A female palm longs for a particular male and begins to ail, although others are closer to her. The Arabs, who are no less familiar with this tree than with their horses and camels, then not only hang the female palms with male flower panicles bearing ripe pollen, but often connect both trunks with a rope.

In addition to male and female flowers, nature also knows hermaphrodite flowers, and all these forms are united and separated in the tree world in many ways. Botanists therefore distinguish a number of sexual variants from hermaphroditism to polygamy.

This is worth mentioning as an indication that gender belongs to the secondary determinations and not to the basic characters, as is confirmed not only by graphology and astrology but also by genetics. The tree as such has a deeper foundation; it bears sexes, but no gender.

For this reason, no valid conclusions can be drawn from the fact that the tree has a male gender in some languages and a female gender in others. This is no more coincidental than the gender given to the sun or the moon, for in the determination lies a statement of the peoples about their peculiarity, similar to that of the individual who records the ideal form of the tree. The conferment of gender in the transition from one language to another is also revealing. + arbor becomes  > arbre; given the close relationship of the two words, this is also curious in that the Romans felt the feminine gender of tree so strongly that they extended it even to species whose names ended in masculine.

Whoever thinks of the tree must not only think of the root, he must also think of the forest. The forest is a faculty of the tree, therefore one can imagine the tree without the forest, but not the forest without the tree.

The forest, however, is not a mere multiplication, not a mere standing together of trees, but it changes the form and life of the individuals. Formed by them, it has an effect on their formation. Selection, as in the wild, becomes more acute; especially in the primeval and mixed forest, the species compete for space and light. For every thousand pollen there is one that fertilises, for every thousand germs there is one stem, and it too is threatened for a long time. In the dense fir forest, one sometimes comes across a young beech that, towering high, bends its crown to the ground. The image is reminiscent of a young man, a pupil who has been expected to do too much.

On the other hand, the forest also provides security. The crowns unite to form a roof which lets the rain through but protects the ground from the sun. The trunks lose their lateral branches and grow upwards in a busy manner. This has an effect on the habitat. Thus, the crown of the free-standing copper beech is already formed close to the ground, while in the copper beech forest the branches only rise to the leaf canopy at a great height like the pointed arches of Gothic columns. Only the trees at the edge of the forest unfurl branches on the outside that reach down to the ground and thus, together with the hedges, form a border wall against the wind that glides over the forest as over a dome. Some forest islands, especially in the tropics, resemble a mighty tree themselves.

The forest grows vigorously with its biomass, giving back to the earth more than it asks of it. Blossoming from year to year, it sheds its leaves and branches, and finally its trunks, to weave them into the humus in which the embers of mighty summers are stored. We still warm ourselves in the abundance of forests whose splendour no human eye has seen.

Only rarely, as in the case of the Andes llama or the breadfruit tree of the South Seas, does the giving virtue become so condensed in a species that the burden of life is almost lifted from the peoples who share its homeland. This is reminiscent of the Golden Age of Hesiod, in which one day’s work was enough to satisfy a year’s need.

It is said of the breadfruit tree that three trunks are enough not only to feed a family year in, year out, but also to provide them with clothing – apart from the timber for the huts, boats, and tools. There are other trees, such as the date and coconut palm, which make deserts and islands habitable, and others without which countries and coastlines would become impoverished – not for nothing was the olive tree considered a gift from the gods.

But even more than the wealth and abundance of fruit under which the branches bend, even more than the donations of wine, bread, sugar, and oil from the trees, man owes the silent growth that forms the trunk year after year and ring after ring. It is in the wood that the salvaging and protective qualities of the tree emerge most unveiled.

It is sometimes said that the Stone Age was preceded by the Wood Age. But it is hardly possible to make a distinction here, for once the inventive sense had awakened in man, everything that offered itself to the need had to become the means: the branch, the pebble, the bone, the horn, the shell, the fishbone. Wood and stone were early combined to form simple tools, usually in such a way that the wood took on the leading role and the stone the harder executive task. We see this in the lances and arrows, the axes and knives of those early times. This is repeated in ever larger contexts up to the half-timbered buildings, in which the wood provides the frame and the stone the filling.

Just as the animal clothes the human being with its fur and wool, the wood not only warms him through fire but also wraps him in an all-embracing garment. It serves him as a table, a boat, a bed in which to rest, to conceive, to give birth and to die, a cradle, and finally also a coffin.

Even today we feel truly at home “in the wood”, be it in the panelled room with its old furniture, be it in the far north, where they still build with wood, in the winter night. Only there do we discover the true life of wood, its forest and tree spirit, its silvestric magic, which not even the axe destroys. It awakens in the fireplace when the annual rings peel off over the embers like pages of a nameless book. There, too, man's memory goes back deep into the only imaginable, into the unseen.

The wood weathers, but it does not lose its living, giving power. For this reason, it seems to many to be more useful as the last garment, the last shell, than the stone sarcophagus. In “Nos habebit humus”1 the trace of man is lost more anonymously and more comfortingly.

But an imperishable element remains. Among the ancients, the coffin was called the bier, bara – the word is ambiguous, since it not only means something to bear, but also something to a load-bearer and a load-carrier. For this reason, the coffin was also regarded as a boat, as a vehicle for the cosmic path, by some peoples who lived far away from each other.

In the singularity, the peculiarity emerges. If one wants to admire the tree and its growth, such as the Jupiter oak in the forest of Fontainebleau, one must allow it space.

In nature, there are all kinds of transitions from more to less dense stands – from impenetrable primeval forests to sparse groves, the forests of the floodplains, dry steppes, prairies, and savannahs, the dissolved schools of the Alpine foothills, as Felix von Hornstein describes them in his work on our forests and their history.

The tree perhaps achieves its most beautiful effect among its peers in the sun-drenched forests where a stand of several hundred years has survived. There the forest rises to a new potency, combining ancient experience and triumph. Space- and time-conquering power becomes palpable as in a senate or an assembly of kings.

Where the tree has been spared in small groups with its undergrowth in the middle of the field, the cultivated land is vigorously revived. Here we are surprised by the sight of plants and animals to which these last islands of wilderness still provide cover, food and shelter.

The row is less a transition to isolation than its intensification. The sight of them evokes the idea of the border, and usually also the protected border. In nature we find them where chains of poplars, alders and old willows accompany the courses of streams and rivers, or in the graceful hems of coconut palms with which the tropical coast greets us from afar.

As a builder, man sets the row to mark his territory and his property. Napoleon had bridges and military roads marked by planting poplars. Stately rows of trees lead to castles, pilgrimage churches, squares where the people of the big cities relax and enjoy themselves; they cut through the parking areas and shade the access roads. Some of these avenues are famous for their length, age and fourfold arrangement; often, like the Herrenhäuser Lindenallee, they connected the capital with the Residenz gardens.

The idea of utilisation recedes in such arrangements. They belong to the princely side of man and his orders. They want to give space to the appearance of the tree and its greatness and lead people to where great and festive things await them, where they worship or rejoice.

Since the tree demands veneration, it has its strongest effect where man, through his art, creates the free space it deserves. This cannot happen overnight. Whoever plants a tree is thinking for grandchildren and great-grandchildren. This includes a caring sense that goes beyond daily consumption and quick use, even beyond one's own life and death. It continues; we feel it in the tranquillity, the peace that makes us happy in an old park. The ancestors have thought of us. We enter into them, remove ourselves from the circles of chasing, threatening time. We feel peace, even in decay. Nuthatches and woodpeckers nest in the hollow trunks, mushrooms settle on the rotten wood, reddish-brown dust trickles from the wormholes. We stroke the bark of the old brother; he has seen tournaments and was already stately when Columbus armed the caravels. There is stronger, dreaming life, and our life itself with its temporal worries becomes a dream. What may remain of them before another century passes?

If, after a period of unlimited use, we protect and cherish the tree, and especially the old tree, we do no more than our duty. This service is not like that of an invalid whom we allow a number of good days in hospital before he retires. In fact, it is not we who protect the tree: it is the tree that gives us its protection. We are allowed to enter it. The old oak, the old lime, the old ash that we honour is a symbol that represents not only the tree of life but also the tree of the world. By not daring to touch them, we testify that the inviolable is honoured and endures. This then also gives meaning and justice to our world and life order. That is why sacrifices had to be made in the past before a tree was felled.

The protective power felt in the tree has been preserved where gods and ancestors are honoured. To commemorate a great person or a twist of fate, we plant a tree. If, as here in Upper Swabia, the crown of an old lime tree catches our eye from afar in the middle of the fields, we can be sure that it is shading an image of a saint or a crucifix and that it will one day fall victim to the storm or lightning rather than the axe.

Myths grasp unity one moment and opposition the next. They grasp the whole and do not omit like science. We must therefore see them stereoscopically. This also applies where they attribute the tree sometimes to the father and sometimes to the mother, sometimes to the earth and sometimes to the gods. Both have their meaning.

The tree is the son of the earth; that is why the priestesses in the Dodona’s grove added the praise of the earth mother to their praise of the supreme Zeus:

Gaea brings forth fruit, therefore praise the earth as mother!

Man has always tried to understand growth and decay in the likeness of the tree - not only his own fleeting life, but also that of the dynasties of princes and gods, of hierarchies and dynasties, of peoples and great empires. All this is driven forth by the eternally young earth, and all falls to it again. It is the great pattern according to which "dying and becoming" is observed and according to which Spengler still proceeds in his comparative observation of cultures. They germinate, blossom, bear fruit, age and die inexplicably as millennial strains, and the earth reclaims them.

There is a reason that we live in a time that is ill-disposed towards the tree. The forests are dwindling, the old trunks are falling, and this cannot be explained by economics alone. Here, economics is only a contributory factor, an executor, because at the same time we live in an age in which there is an unheard-of amount of waste. This corresponds to its two great tendencies: levelling and acceleration. The higher must fall, and the ancestral loses its power. The tree in its height belongs to the father, and with it falls much that was worthy of the father: the crown, the sword of war and the sword of judgement, the sacred borders and the horse.

The myth, however, recognises in the tree not only the tree of life but also the tree of the world. Rooted in the primordial ground, blossoming in the cosmos, it brings forth stars and suns. Father and mother are united in eternal splendour. This is the wood of life in the centre of the Eternal City, where there is no separation, no sanctuary. Therefore, the ash tree Yggdrasil, in whose shade the gods gather daily to hold council, shall not fall with them: it survives the fall.

“The earth will have us.”