From Die Kommenden Titanen

Published in 2002

Part One is available here:

Part Two is available here:

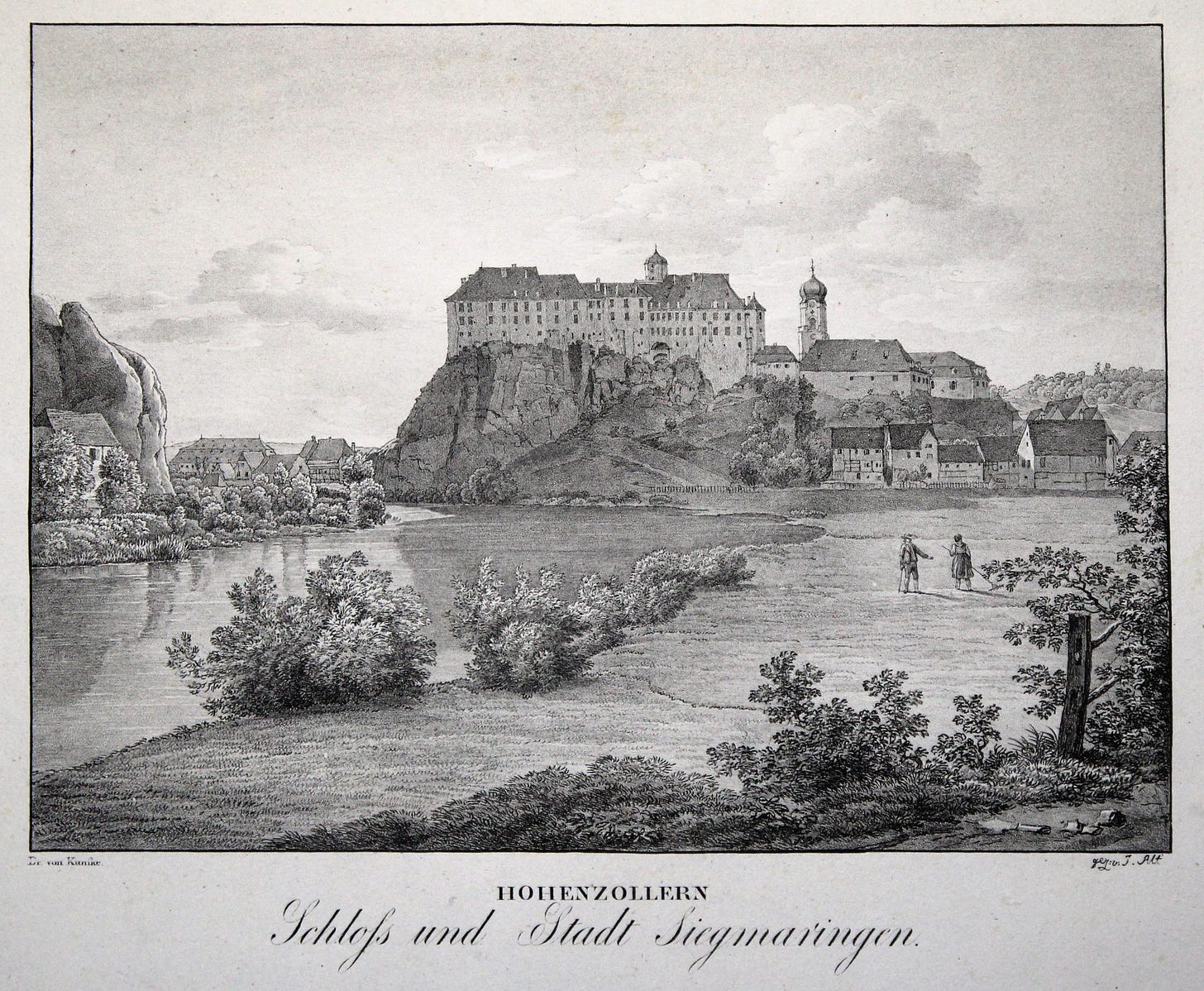

Sunday, 15 October. The pale autumn sun has dispersed the fog, and Sigmaringen Castle shines in the milky light, perched on the hill on which the town sits. Below, in the castle grounds, flows the Danube, which here is still only an inconspicuous rivulet. For the few kilometres that separate us from Wilflingen we drive along a forest road, which at this time is completely deserted. Before reaching the village we pass a cemetery where we stop briefly at the graves of Greta, Jünger's first wife, and Ernst and Alexander, his two sons. Jünger attached great importance to the cult of the dead and always passed by during his daily walks.

When we arrived, he was already waiting for us. He is in good spirits and in great shape. He walks briskly back and forth between the study and the living room. He sits us down at the table with coffee and biscuits. He asks us a few questions today. He knows that we have been in Frankfurt for the last few days for the book fair, and he asks if we have seen Carl Schmitt's correspondence with Armin Mohler, which he has heard about and is interested in reading because it contains many things he is very excited about. He also wants to know about the controversy surrounding the hypothetical invitation of the mayor of Venice to celebrate his centenary in the city of Laguna. He is curious about Italy, about what is happening in our country. It is a curiosity that comes from the depths of his soul, from an aspiration born in his youth. So first we ask him to recall those years.

In the 1920s you spent some time in Naples. How did you like it there?

I enjoyed it very much. It was an interesting experience for me, not least because travelling abroad in those days was much more adventurous than it is today. I lived in the upper part of the city, overlooking the Castel del Ovo castle below, in a guesthouse run by a German woman who received guests who came to visit or work at the aquarium, where I also worked as a researcher at the zoological station founded by Anton Dorn. Even at that time Naples was already a very chaotic city and I liked to get around on foot. I loved walking through the narrow streets of the Spanish neighbourhoods and observing people's lives. I had a similar experience in 1986 in Palermo, walking through the old town.

This early experience and your subsequent study of zoology and botany show your great interest in nature...

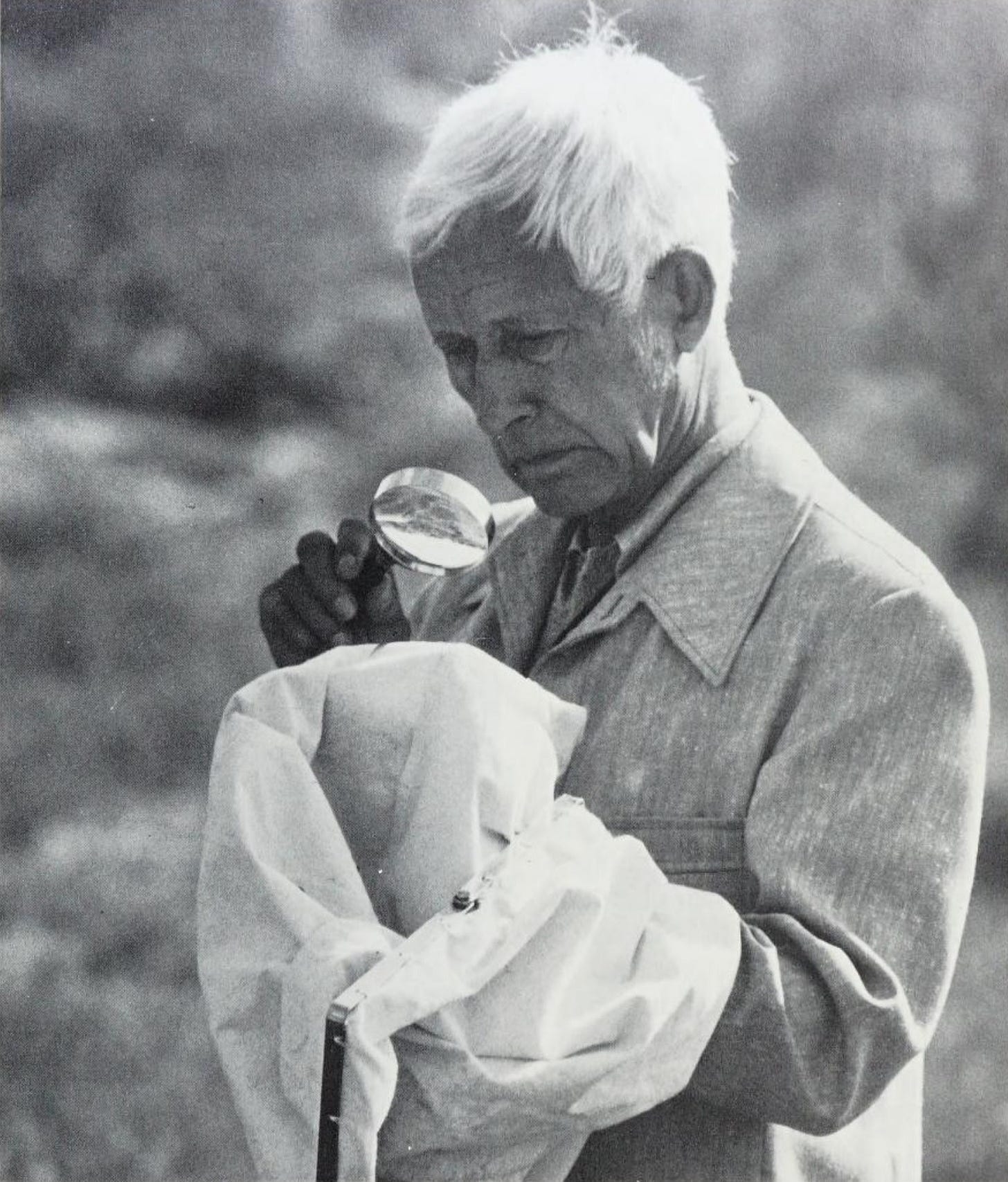

Yes, nature is something that has always occupied me. People usually think of me as a writer and my fascination with entomology as an extravagance. But for me, they are two equal passions that I cannot separate. Observing life in nature, whether on a small or large scale, is an amazing sight and an activity that gives me peace of mind. I have a passion for insects, but I also love plants. In Paris during the war, I often went on botanical excursions to the Bois de Boulogne forest. When the Americans entered the city, I was surprised during one such excursion. Finally, it was also a spiritual activity to escape from the sad reality of war.

So entomology is not just a hobby for you?

No, it's more than that. It is a passion that I have been fond of since my youth, which I continue to cultivate today and to which I attach deep meaning. I called one of my collections of aphorisms "Maxima - Minima" to denote the two dimensions of being, of nature, that are at the centre of my observations. My passion for bugs goes in the direction of micro-dimensionality. And then there is the passion to explore the great unknowns of the universe, the maximal problems. Also, the insect world can be studied in the same way as the human and social world. Insects, bees, and ants have their own well-organised social life, which is interesting to observe.

I am curious, why insects?

This was the question that Gide asked me when I told him about my fascination. I replied that beetles, with their shells, seemed to me the strongest insects. And Gide: "I understand that very well.” But I also love them for the distinctness of their lines and shapes. They are a kind of jewellery of the earth. Their beauty is not immediately visible, it is not dazzling like butterflies, but on the other hand, the passion we feel for them lasts a long time.

Speaking of passion, many people have been fascinated by your books. Herman Hesse, for example, wrote a flattering review of your work. Did you meet him personally?

No, he was already living in Switzerland when he wrote his review and we didn't have the opportunity to meet. Hesse used to write a letter on New Year's Day and send it to all his friends. In one of these letters he mentioned me. The book An der Zeitmauer made the greatest impression on him, in which he found some similarities with his conviction that we are at the end of a historical epoch and on the threshold of a new epoch. And that is not all: one of the ideas I expressed in that book, which impressed him, was that in order to understand what is happening we need to shift our gaze, so to speak, from human history to the history of the Earth, to move from the consideration of historical time to cosmic time, the time of nature. Man is part of the events of the cosmos. At one point Hesse makes an interesting observation: he admits that he does not know whether what I am describing is true or not, but that what I am writing gives him the impression that he is participating in the spectacle I am describing. I see this as a great recognition, especially when expressed by a writer like him. His whole life, like mine, intersects with the dilemma between action and contemplation, and this common problem has created an opportunity for understanding.

Which of Hesse's texts have you read and appreciated the most?

I read Hesse most passionately in the 1920s. I read Siddhartha and Steppenwolf, of course, as well as Narcissus and Goldmund, and after the war The Glass Bead Game.

What other authors were you fascinated by?

I particularly remember some French writers. For example, Léon Bloy, whom I read intensively and who inspired me. Being awarded the title of "honorary member" of the Society for the Study of Bloy's work was a very pleasant recognition for me. It was Carl Schmitt who advised me to read this “intolerant Catholic,” as he was called. I have read his diaries and at least a few times the small book Von den Juden das Heil. It is a text that introduces us to the mysteries of magical and sacred power, in which Bloy appears to me as an electrician who handles high-voltage wires too lightly. One gets the impression that at any moment there could be an electric shock and everything could burst into flames. Among Bloy’s phrases that have had the strongest impact on me, there is one magnificent one that I picked up and commented on in An der Zeitmauer: “Dieu se retire” (“God is leaving”). This phrase succinctly but effectively describes what is happening with the rise of nihilism, with the rejection of God by modern man. This phrase should be read in conjunction with Nietzsche's statement that “God is dead.”